For the past decade and a half, Ernest Hilbert has worked as a librettist with composers, including two productions with composer Stella Sung. You may stream full performances of both of their operas below.

Stella Sung’s setting of poems from Hilbert’s book High Ashes, “High Ashes for Baritone and Orchestra,” was performed by the Fox Valley Symphony Orchestra on Saturday, September 27th, 2024, with baritone Maximillian Krummen, conducted by Kevin Sütterlin. It was commissioned as a companion piece to Gustav Mahler’s “Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen,” “Songs of a Wayfarer.”

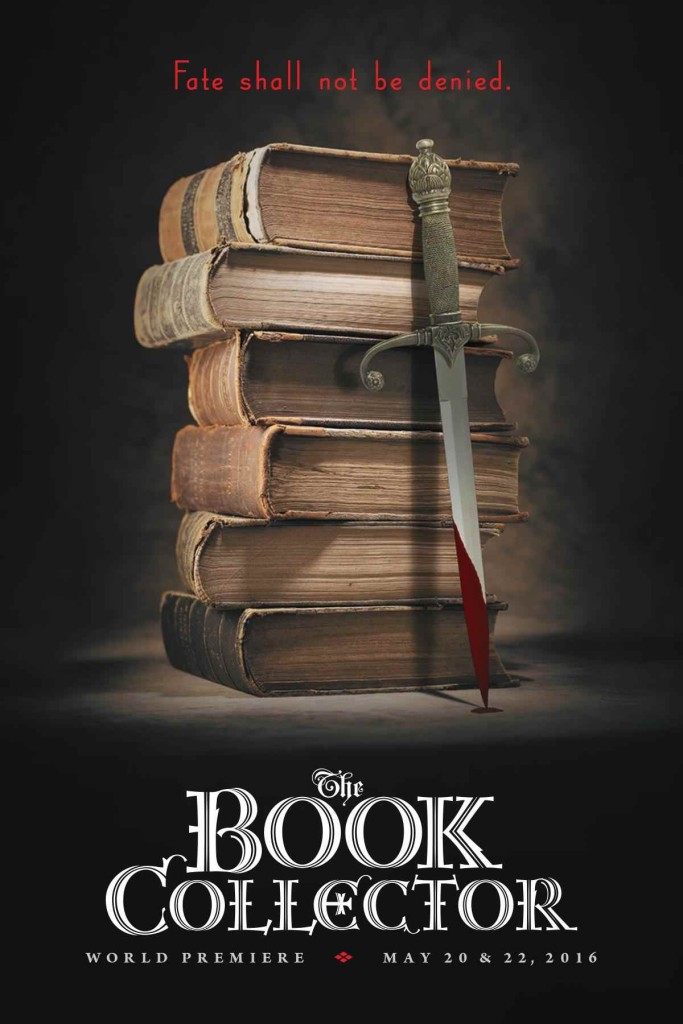

Hilbert’s most recent opera with composer Stella Sung, The Book Collector, premiered at the Dayton Opera on Friday, May 20th, 2016, with a matinee performance on Sunday May 22nd. Joe Law wrote in Opera News that “Sung and her librettist Ernest Hilbert have imagined a scenario explaining how the manuscript that Orff used for his texts came to be in the monastery at Benediktbeuren . . . The Book Collector is an effective piece of musical theater.” The opera incorporated physical stage settings with virtual 3D digital backdrops, a ballet sequence, and full orchestra with choir. Commissioned by Dayton Performing Arts Alliance in 2013 as a prologue to Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana, The Book Collector is a one-act Gothic tale of unforeseen fortunes and ancestral madness, young love and powerful obsession, played out against the backdrop of the Bavarian city of Bamberg—known across Europe as the “Franconian Rome” for its seven hills, each crowned with a beautiful church—at the start of the nineteenth century.

The dashing and impulsive Baron Otto von Schott, long a recluse in his fortress, hopes to finally complete his collection of arcane books with the addition of a final mysterious volume, but he finds himself thwarted by Franz Bierman, a shrewd young bookseller. The enraged Baron plots revenge, ultimately entangling his lonely, unsuspecting daughter Anna in his deranged scheme to retrieve the book from the bookseller. Franz and Anna find themselves falling in love, and, after the unexpected intercession of a silent, enigmatic monk, the Baron’s madness deepens until it is finally too late for him to turn away from his own fate.

The Book Collector was commissioned by the Dayton Opera and Ballet, and funded in part by the League of American Orchestras, New Music USA, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Francis Goelet Charitable Lead Trusts, the Aaron Copland Fund for Music, and the ASCAP Foundation. The opera, which incorporates 3-D digital technology and a ballet, is intended as companion piece to Carl Orff’s scenic cantata Carmina Burana. It will premiere in May, 2016.

The production featured tenor Andrew Owens as Franz Bierman, soprano Angela Mortellaro as Anna von Schott, and bariton Andrew Garland as Baron Otto von Schott, along with stage director Gary Briggle, conductor Neal Gittelman, artistic director Thomas Bankston, chorus director Hank Dahlman, choreographer Karen Russo, and the Dayton Philharmonic Orchestra, Chorus, and Ballet.

Synopses for Hilbert’s operas appear below, as well as Hilbert’s essays on the art of the libretto.

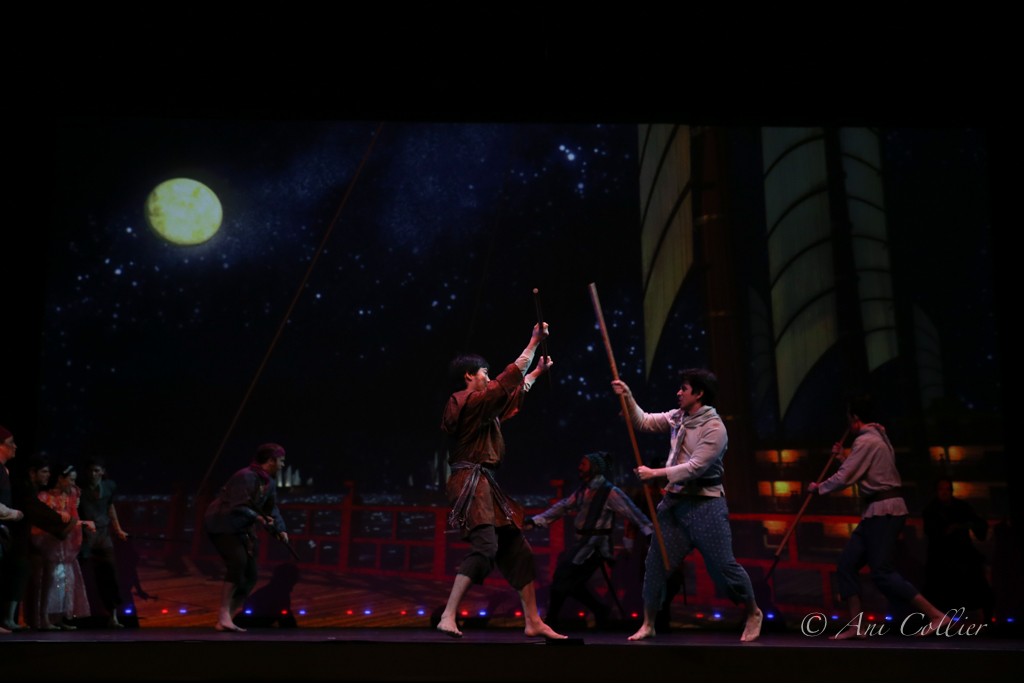

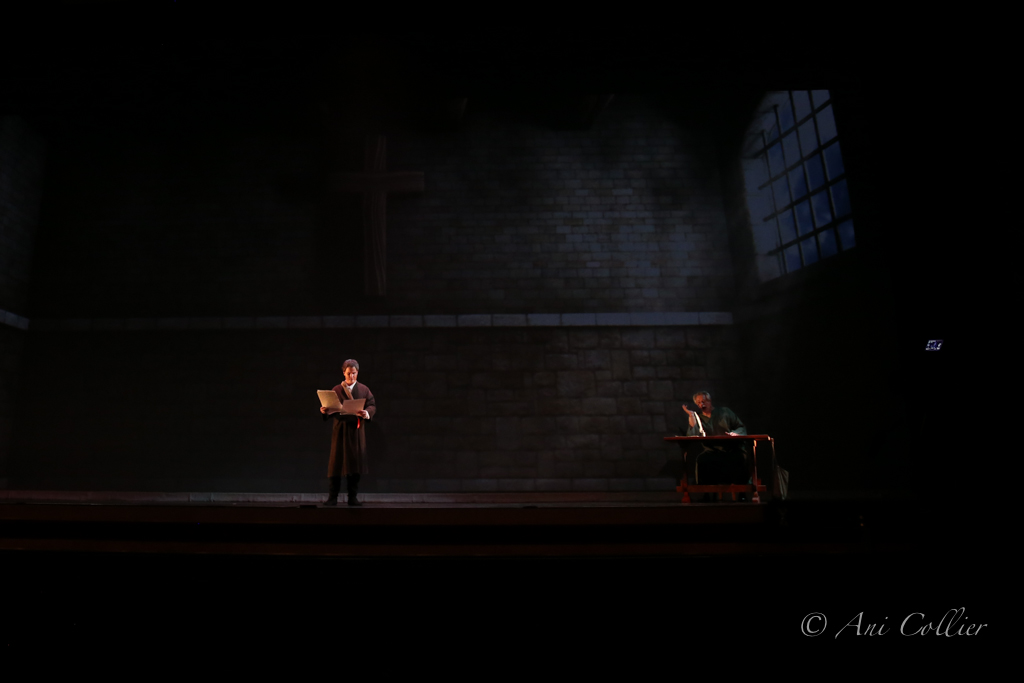

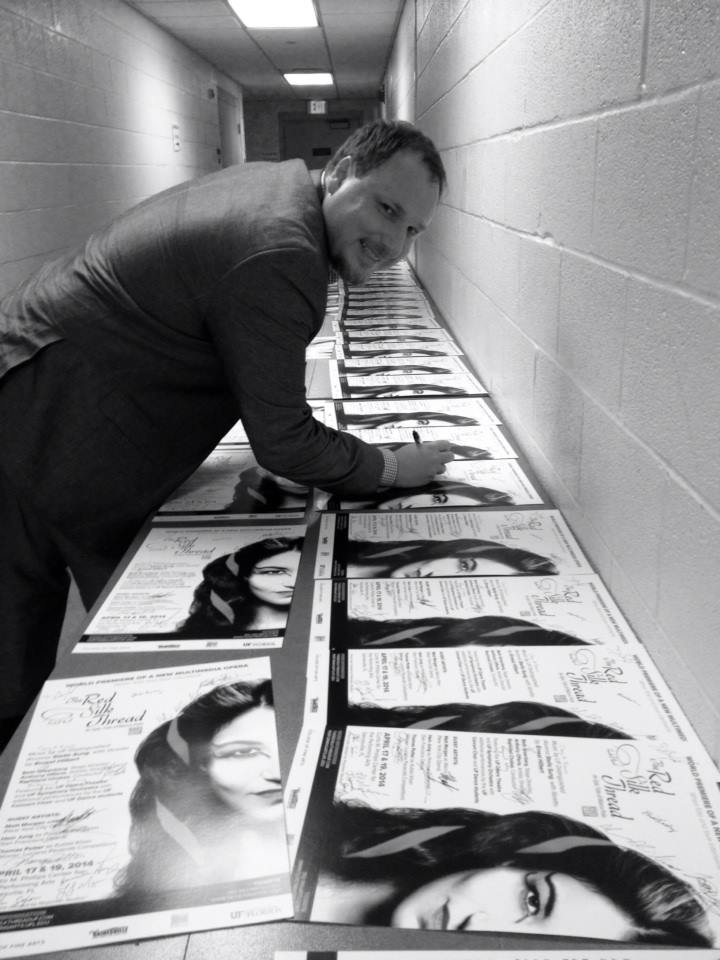

Hilbert supplied the story and libretto for an evening-length, three-act opera with composer Stella Sung titled Red Silk Thread: An Epic Tale of Marco Polo (later retitled Marco Polo: Tale of the Red Silk Thread), a historical drama set in the court of Kublai Khan. Workshop performances of the opera took place at the Michigan Opera Studio in April 2013, directed by Robert Swedberg with musical director Kathryn Goodson and starring Jacob Wright, Alan Nagle, Imani Mchunu, Natalie Doran, Amanda O’Toole, and Katie Nadolny, with 3-D digital backdrops created by Ninjaneer Studios.

Red Silk Thread: An Epic Tale of Marco Polo premiered in April, 2014 at the Curtis M. Phillips Center for the Performing Arts in Florida, starring Matt Morgan, Hein Jung, and Thomas Potter, featuring a large on-stage cast, 80-piece orchestra and 60-voice offstage choir, directed by Beth Greenberg, conducted by Raymond Chobaz, with Chorus Master Will Kesling, along with choreographers, digital effects professionals, costume designers, animators, répétiteurs, lighting designers, and fight coordinators.

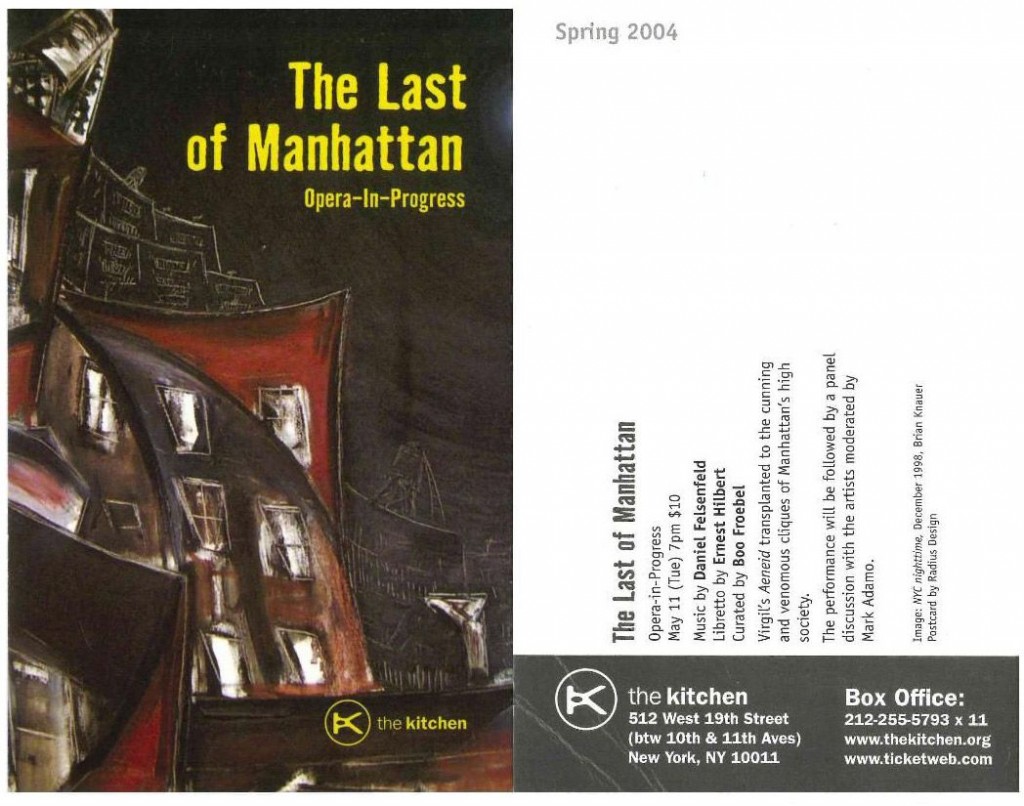

Hilbert supplied libretti for several pieces by avant-garde New York composer Daniel Felsenfeld, including the operas Summer and All it Brings and The Last of Manhattan, and the song cycle The Bridge, which have been performed by the New York City Opera at Symphony Space, the Bowery Poetry Club, the Kitchen, VisionIntoArt, Proshansky Auditorium, Make Music New York Festival, The Stone (Ferus Music Festival), St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, and Grace Episcopal Church, all in New York City. After the May 2004 performances of The Last of Manhattan, critic Marion Lignana Rosenberg wrote in Time Out New York that “Troy has inspired its share of operas, among them Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas, Berlioz’s Les Troyens, and Gluck’s Paride ed Elena. Now from New York composer Daniel Felsenfeld and poet Ernest Hilbert comes The Last of Manhattan, a cheeky, literate riff on Purcell’s Dido. The titular lovesick queen of Carthage becomes Victoria Wells, real-estate czarina; Aeneas, refugee from Troy and fated founder of Rome, is recast as Kenneth Sexton, Australian media magnate. Purcell’s witches are Paris Hilton types—snarky socialites with too much time on their hands. Instead of the blood-soaked soil of the Italic Peninsula, Manhattan air rights are in play. Hilbert’s elegant verse and Felsenfeld’s lush, beautifully wrought music make this 21st-century addition to the 3,000-year-old (and counting) Trojan canon one not to be missed.”

Hilbert provided lyrics for the song cycle Vignettes of Two Lovers for composer Christopher LaRosa. LaRosa also set four poems from Hilbert’s book Sixty Sonnets and used Hilbert’s poem “Symmetries” as a prologue to his composition of the same name. LaRosa’s music for strings and harp appears on the last quarter of Hilbert’s spoken word album Elegies & Laments (Pub Can Records, 2013).

Backstage at the premiere of Marco Polo: Tale of the Red Silk Thread, Hilbert happily signs 100 copies of the official concert poster for donors and other supporters.

Hilbert has also worked with indie rock bands. In 2009, he appeared on stage as a special guest with the rockabilly-punk band Mercury Radio Theater at the Khyber Pass rock club in Philadelphia, providing a live reading to accompany both the band and an animated film created for the occasion. Hilbert also appeared in a short film, co-written with Kurt Alford Fowler, screened onstage at the “Death of Mercury Radio Theater,” an evening of rock bands and burlesque routines at Philadelphia’s Johnny Brenda’s rock club in 2011.

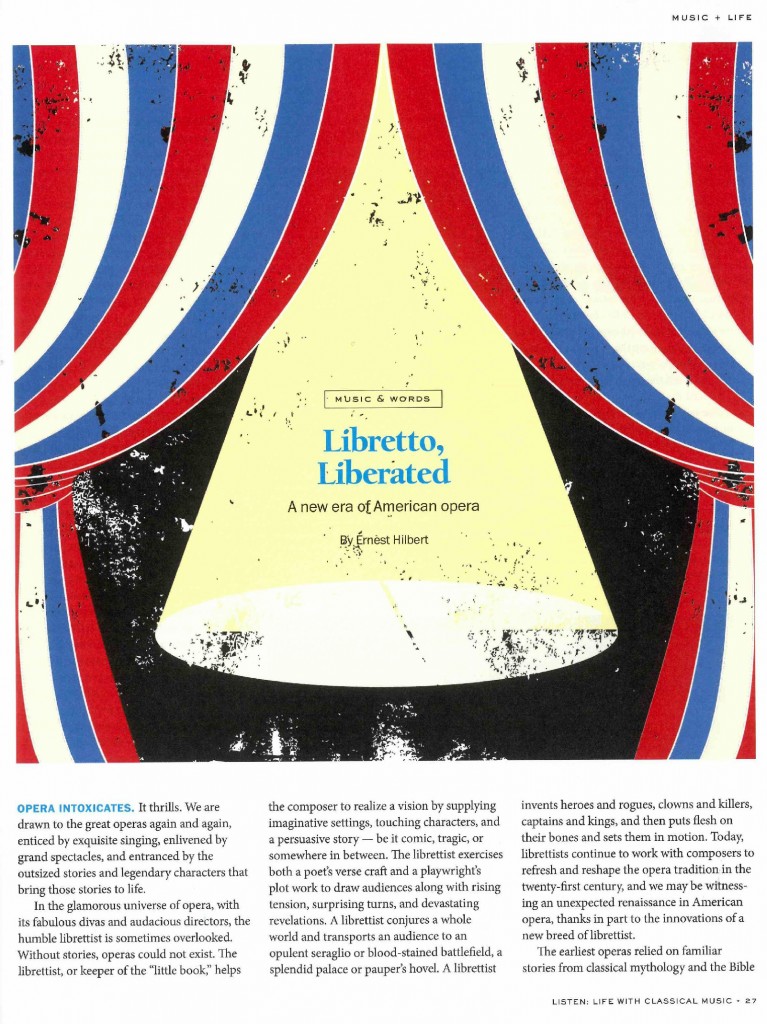

Hilbert’s essay “Libretto, Liberated: A New Era of American Opera” appeared in the summer 2014 issue of Listen Magazine, exploring the possibility that America may enter an era of new opera driven as much by librettists as by composers. Esteemed classical music critic John J. Puccio writes that “the thorough and insightful poet Ernest Hilbert posits that a new crop of librettists, with a knack for historical speculation and imaginative storytelling, are major drivers of a new era of American opera.”

“Libretto, Liberated, a New Era of American Opera”

By Ernest Hilbert

Opera intoxicates. It thrills. We are drawn to the great operas again and again, enticed by exquisite singing, enlivened by grand spectacles, and entranced by the outsized stories and legendary characters that bring those stories to life.

In the glamorous universe of opera, with its fabulous divas and audacious directors, the humble librettist is sometimes overlooked. Without stories, operas could not exist. The librettist, or keeper of the “little book,” helps the composer to realize a vision by supplying imaginative settings, touching characters, and a persuasive story—be it comic, tragic, or somewhere in between. The librettist exercises both a poet’s verse craft and a playwright’s plot work to draw audiences along with rising tensions, surprising turns, and devastating revelations. A librettist conjures a whole world and transports an audience to an opulent seraglio or blood-stained battlefield, a splendid palace or pauper’s hovel. A librettist invents heroes and rogues, clowns and killers, captains and kings, and then puts flesh on their bones and sets them in motion. Today, librettists continue to work with composers to refresh and reshape the opera tradition in the twenty-first century, and it is possible that we are witnessing an unexpected renaissance in American opera, thanks in part to the innovations of a new breed of librettist.

The earliest operas relied on familiar stories from classical mythology and the Bible as well as grand historical episodes: consider Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo (1607) and Handel’s Giulio Cesare (1724). Later generations adapted popular plays, poems and novels. For the libretto of Mozart’s ever-magical Le Mariage de Figaro, Lorenzo Da Ponte—possibly the greatest of all librettists [see “Words, words, words” and “Mozart’s unbeatable three,”] Vol. 3, No. 1, LISTEN Magazine]—essentially restyled Beaumarchais’s 1784 stage comedy La Folle Journée, ou le Mariage de Figaro scene for scene, keeping “its jewel-machined precision intact,” as librettist J.D. McClatchy puts it, while blunting the sharper political edges (though retaining what Bridig Brophy in Mozart the Dramatist terms Count Almaviva’s “tyrannical eroticism”). Da Ponte condensed the play’s action into four acts, reduced the number of characters, and otherwise tailored it to the opera, but he felt no pressing need to depart much from the original work. When librettists Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy adapted Prosper Mérimée’s 1845 novella Carmen for Bizet’s famous opéra comique, however, they felt compelled to reorganize the story significantly, though they preserved much important detail. English poet W.H. Auden actually took inspiration for Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress from William Hogarth’s famous series of allegorical engravings, depicting the downfall of a young gentleman, a rare example of the visual arts inspiring an opera (the idea germinated with Stravinsky).

At other times, life and literature conspire felicitously, even ferociously, to inspire an opera. Richard Wagner’s Der fliegende Holländer derives from an 1831 short story by Heinrich Heine (“Aus den Memoiren des Herren von Schnabelewopski”), itself taken from a stage play. You could say the story was in the air at the time. However, it wasn’t until Wagner found himself on a small, creaky ship called the Thetis, as it was battered by a fearsome storm off Skagerrak, that he was truly moved to create his Dutchman. Some modern composers follow Wagner’s example and supply their own librettos, though professional librettists might compare that to acting as one’s own lawyer. (In his now-forgotten handbook, The Art of Writing Opera-librettos: Practical Suggestions, Edgar Istel intimates that Wagner only wrote his own texts because he didn’t know any good librettists, though this notion is likely fanciful as it is unthinkable that Wagner could have achieved his enormous breakthroughs while wrangling with a convention-bound librettist along the way.) Successful collaborations often yield results far more accomplished than anything either artist could have achieved alone. It is impossible to imagine the opera repertoire stripped of the great composer–librettist collaborations: Mozart with Da Ponte, Puccini with Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa, Richard Strauss with Hugo von Hofmannsthal. By the twentieth century, one even begins to think of collaborative teams as brand names: Gilbert and Sullivan, Rogers and Hammerstein.

Operas are expensive cooperative enterprises. They were risky investments even in their heyday and are now both labors of love and money pits. McClatchy has quipped that “the only thing more expensive than opera is war.” In this regard, operas resemble CGI-heavy Hollywood blockbusters, which frequently rely on “pre-sold” stories and characters, or at the very least A-list actors familiar to audiences the world over. This makes sense. When much is at stake, it pays to be conservative. New operas can be woven from proven stories, such as Nobel Laureate Toni Morrison’s libretto for Richard Danielpour’s 2005 opera Margaret Garner, which was adapted from her own best-selling novel Beloved, itself a retelling of a heartbreaking historical incident. After the opera was finished, Morrison declared she would never stray into the realm of opera again, remarking to David Patrick Stearns of the Philadelphia Inquirer that “it’s apart from the work that I really and truly must do and is too important to be a secondary thing. . . . And if you can’t commit with that kind of intensity, and revisions, and deal with the business world of it, you shouldn’t contend.” New operas developed from classic stories also continue to appear with some frequency. Tarik O’Regan’s Heart of Darkness with libretto by Tom Phillips emerges from Conrad’s celebrated novella. For Robert Aldridge’s 2008 opera Elmer Gantry, librettist Herschel Garfein adapted Sinclair Lewis’s 1927 satirical novel about a shady Christian evangelist who finds great success despite his own bad behavior. Led Zeppelin bassist John Paul Jones has announced he is working on an operatic adaptation of Strindberg’s play Spöksonaten (The Ghost Sonata). Today, librettists adapt not only literary properties but also films, such as Kevin Puts and librettist Mark Campbell’s 2011 opera Silent Night, from the 2005 film Joyeux Noël, about the Christmas truce during the First World War. Perhaps it is only a matter of time before the first opera based on a video game. Grand Theft Auto: An Opera in Two Acts? Good stories, new and old, appeal to opera audiences. Nonetheless, according to Opera America, the most commonly produced operas of recent years are all old household names, all composed a century or two ago: Mozart’s Figaro and Magic Flute; Puccini’s La bohème, Tosca, and Madama Butterfly; Bizet’s Carmen; Verdi’s La traviata; and Humperdinck’s Hänsel und Gretel.

Operas are expensive cooperative enterprises. They were risky investments even in their heyday and are now both labors of love and money pits. McClatchy has quipped that “the only thing more expensive than opera is war.” In this regard, operas resemble CGI-heavy Hollywood blockbusters, which frequently rely on “pre-sold” stories and characters, or at the very least A-list actors familiar to audiences the world over. This makes sense. When much is at stake, it pays to be conservative. New operas can be woven from proven stories, such as Nobel Laureate Toni Morrison’s libretto for Richard Danielpour’s 2005 opera Margaret Garner, which was adapted from her own best-selling novel Beloved, itself a retelling of a heartbreaking historical incident. After the opera was finished, Morrison declared she would never stray into the realm of opera again, remarking to David Patrick Stearns of the Philadelphia Inquirer that “it’s apart from the work that I really and truly must do and is too important to be a secondary thing. . . . And if you can’t commit with that kind of intensity, and revisions, and deal with the business world of it, you shouldn’t contend.” New operas developed from classic stories also continue to appear with some frequency. Tarik O’Regan’s Heart of Darkness with libretto by Tom Phillips emerges from Conrad’s celebrated novella. For Robert Aldridge’s 2008 opera Elmer Gantry, librettist Herschel Garfein adapted Sinclair Lewis’s 1927 satirical novel about a shady Christian evangelist who finds great success despite his own bad behavior. Led Zeppelin bassist John Paul Jones has announced he is working on an operatic adaptation of Strindberg’s play Spöksonaten (The Ghost Sonata). Today, librettists adapt not only literary properties but also films, such as Kevin Puts and librettist Mark Campbell’s 2011 opera Silent Night, from the 2005 film Joyeux Noël, about the Christmas truce during the First World War. Perhaps it is only a matter of time before the first opera based on a video game. Grand Theft Auto: An Opera in Two Acts? Good stories, new and old, appeal to opera audiences. Nonetheless, according to Opera America, the most commonly produced operas of recent years are all old household names, all composed a century or two ago: Mozart’s Figaro and Magic Flute; Puccini’s La bohème, Tosca, and Madama Butterfly; Bizet’s Carmen; Verdi’s La traviata; and Humperdinck’s Hänsel und Gretel.

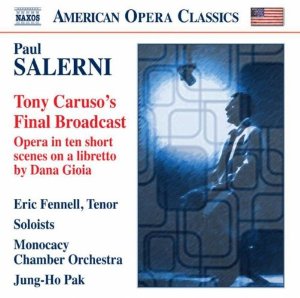

Librettist Dana Gioia, who supplied the original story and libretto for Paul Salerni’s poignant opera Tony Caruso’s Final Broadcast (2004), has remarked that “opera is the form that [gives] the poet most imaginative freedom.” This may be true, but one problem with adaptations is that audiences expect characters, situations, and basic story lines to carry over from other art forms more or less intact. Subtle shading by a librettist may persuade an audience to see a character’s motivation in a new light. Careful alterations of a plot may refocus one theme and jettison another. But the story arrives prefabricated—there is only so much a librettist can do. In an effort to refresh old stories and breathe new life into stock types, directors sometimes craft wildly inventive productions that radically alter settings or use outrageous costuming to stimulate audiences grown bored with conventional opera house fare. New Yorker music critic Alex Ross recently pronounced that “if opera houses paid more heed to new music, Regietheater would be redundant; it’s because we endlessly repeat the same old pieces that we feel the need to reinvent them in ever more drastic fashion.”

Librettist Dana Gioia, who supplied the original story and libretto for Paul Salerni’s poignant opera Tony Caruso’s Final Broadcast (2004), has remarked that “opera is the form that [gives] the poet most imaginative freedom.” This may be true, but one problem with adaptations is that audiences expect characters, situations, and basic story lines to carry over from other art forms more or less intact. Subtle shading by a librettist may persuade an audience to see a character’s motivation in a new light. Careful alterations of a plot may refocus one theme and jettison another. But the story arrives prefabricated—there is only so much a librettist can do. In an effort to refresh old stories and breathe new life into stock types, directors sometimes craft wildly inventive productions that radically alter settings or use outrageous costuming to stimulate audiences grown bored with conventional opera house fare. New Yorker music critic Alex Ross recently pronounced that “if opera houses paid more heed to new music, Regietheater would be redundant; it’s because we endlessly repeat the same old pieces that we feel the need to reinvent them in ever more drastic fashion.”

New operas, particularly ones based on original scenarios or imagined from historical episodes rather than known stories, invigorate the repertoire and challenge audiences, but they are rare. The great benefit of writing original scenarios is that both librettist and composer may shake off old stereotypes and conventions and create dramatic structures from the ground up for contemporary audiences, rather than attempting to drag old stories, however powerful they may be, into the twenty-first century. A new generation of librettists has begun to work outside the tradition of adaptation, and there are indications that this new wave of operas may eventually change the repertoire significantly. Some develop a story directly from the historical record. John Adams’s large-scale operas Nixon in China, the ever-controversial Death of Klinghoffer, and Doctor Atomic (the first two with librettos by Alice Goodman, who withdrew from the third, leaving director Peter Sellars to supply the text) all draw on iconic and provocative historical episodes. The characters and their predicaments are familiar. The story is in place, but the librettist is expected to fill in parts of the history we could not possibly know. My own libretto for Stella Sung’s evening-length opera The Red Silk Thread, about Marco Polo in the court of Kublai Khan, owes its original story to the broad contours of the rather hazy written histories of the period. McClatchy formulated a sequence of dramatic tableaux sketched from Vincent van Gogh’s letters for Bernard Rands’s 2011 opera Vincent in order give a “vivid portrait” of “the contours of [van Gogh’s] conflicted soul,” according to Benjamin R. Barber (The Huffington Post, 11 April 2011). Composer Tom Cipullo wrote the libretto for his own opera Glory Denied, drawn from Tom Philpott’s non-fiction book Glory Denied: The Saga of Jim Thompson, America’s Longest-Held Prisoner of War. Here we have examples of opera beginning with historical speculation, private correspondence, and non-fiction biography, but there are many other routes to new opera.

New operas, particularly ones based on original scenarios or imagined from historical episodes rather than known stories, invigorate the repertoire and challenge audiences, but they are rare. The great benefit of writing original scenarios is that both librettist and composer may shake off old stereotypes and conventions and create dramatic structures from the ground up for contemporary audiences, rather than attempting to drag old stories, however powerful they may be, into the twenty-first century. A new generation of librettists has begun to work outside the tradition of adaptation, and there are indications that this new wave of operas may eventually change the repertoire significantly. Some develop a story directly from the historical record. John Adams’s large-scale operas Nixon in China, the ever-controversial Death of Klinghoffer, and Doctor Atomic (the first two with librettos by Alice Goodman, who withdrew from the third, leaving director Peter Sellars to supply the text) all draw on iconic and provocative historical episodes. The characters and their predicaments are familiar. The story is in place, but the librettist is expected to fill in parts of the history we could not possibly know. My own libretto for Stella Sung’s evening-length opera The Red Silk Thread, about Marco Polo in the court of Kublai Khan, owes its original story to the broad contours of the rather hazy written histories of the period. McClatchy formulated a sequence of dramatic tableaux sketched from Vincent van Gogh’s letters for Bernard Rands’s 2011 opera Vincent in order give a “vivid portrait” of “the contours of [van Gogh’s] conflicted soul,” according to Benjamin R. Barber (The Huffington Post, 11 April 2011). Composer Tom Cipullo wrote the libretto for his own opera Glory Denied, drawn from Tom Philpott’s non-fiction book Glory Denied: The Saga of Jim Thompson, America’s Longest-Held Prisoner of War. Here we have examples of opera beginning with historical speculation, private correspondence, and non-fiction biography, but there are many other routes to new opera.

Colorado poet laureate David Mason recently turned to the art of the libretto. Mason’s operas include a spirited adaptation of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s novel The Scarlet Letter with composer Lori Laitman, and an adaptation, also with Laitman, of his own book-length poem Ludlow, which chronicles the labor disputes in a Colorado mining community that led to the infamous “Ludlow Massacre” of 1914. After receiving a commission from Seattle’s Music of Remembrance, Mason began work on a new opera with Tom Cipullo on the subject of the Holocaust. They chose to construct a bizarre and entirely invented conversation between Gertrude Stein and Pablo Picasso, both of whom survived the Second World War in Vichy and Nazi–occupied France in relative comfort. “I realized that these two estranged friends,” says Mason, “two major artists of the twentieth century and, arguably, two outsized egomaniacs, would provide me a great opportunity to explore the culpability of artists in Vichy and occupied France.” Mason felt this scenario would quickly get to the heart of his difficult subject in a manner that remains relevant today: “What is the position of art in a time of war? How does art respond to political and military disaster? And what can artists possibly do in the face of such massive evils as Nazism and the Holocaust?” When the two eminent modernist artists are confronted by a young orphan, speaking to them from a concentration camp, Picasso pleads “I was in Paris. So far away,” followed by Stein, “I couldn’t have known.” The finished opera, which will premiere May 2015, promises to be powerful and unsettling.

This fascination with violence and its political consequences is shared by publisher and poet Kate Gale, who worked with Don Davis, an orchestral composer who scored the Matrix film trilogy, on an opera in Spanish addressing the overthrow of Latin American governments. Río de Sangre received its 2010 premiere with the Florentine Opera Company in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Fanfare’s Barnaby Rayfield describes the opera as “a fable of corrupted idealism and political cynicism.” Kate Gale’s libretto, about a South American idealist and revolutionary caught up in an endless cycle of power and violence, was translated into Spanish for the musical setting by Alicia Partnoy, herself survivor of the secret detention camps in which about thirty thousand Argentines disappeared. Gale and Davis opted for the freedom of an original scenario rather than adapting an existing property because “many composers and librettists choose to use fictional characters and situations to offer a general commentary on political and historical events, aiming for a degree of universality.” The central character, Delacruz, begins the opera singing from his palace balcony, appealing to the crowd for “La libertad de la tiranía y de la opresión” (“Freedom from tyranny and oppression”). In an ominous turn worthy of Gabriel García Márquez, the opera concludes with a new freedom fighter singing the same phrase from the same balcony.

This fascination with violence and its political consequences is shared by publisher and poet Kate Gale, who worked with Don Davis, an orchestral composer who scored the Matrix film trilogy, on an opera in Spanish addressing the overthrow of Latin American governments. Río de Sangre received its 2010 premiere with the Florentine Opera Company in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Fanfare’s Barnaby Rayfield describes the opera as “a fable of corrupted idealism and political cynicism.” Kate Gale’s libretto, about a South American idealist and revolutionary caught up in an endless cycle of power and violence, was translated into Spanish for the musical setting by Alicia Partnoy, herself survivor of the secret detention camps in which about thirty thousand Argentines disappeared. Gale and Davis opted for the freedom of an original scenario rather than adapting an existing property because “many composers and librettists choose to use fictional characters and situations to offer a general commentary on political and historical events, aiming for a degree of universality.” The central character, Delacruz, begins the opera singing from his palace balcony, appealing to the crowd for “La libertad de la tiranía y de la opresión” (“Freedom from tyranny and oppression”). In an ominous turn worthy of Gabriel García Márquez, the opera concludes with a new freedom fighter singing the same phrase from the same balcony.

Could we be in the midst of a new era of American opera? There are certainly signs that we are. The flourishing movement toward new opera is remarkably, and perhaps beneficially, decentralized. Numerous funding bodies around the nation—including American Composers Forum, the Composer-Librettist Studio, New Music USA, and CCi-Composers Collaborative—pair librettists with composers and serve as models for the promotion of new operas. Beth Morrison Projects, founded by producer Beth Morrison, organizes the Prototype: Opera/Theater/Now festival at Here Arts Center in Manhattan. Now in its second year, the festival presents five new “ready-to-travel productions of innovative new operas,” most staged, some in concert form in order to attract funding. The Metropolitan Opera’s Commissioning Program’s 2009 workshop of Nico Muhly’s disturbing, internet-age opera Two Boys, with libretto by Craig Lucas, led to its Met premiere in the fall of 2013. The house’s general manager, Peter Gelb, remarked in the New York Times that “for opera to be significant as an art form, it’s absolutely essential that we do present new work,” because, he believes, new opera “brings a new audience into the theater.”

In any age, many works of art are created, most of which fizzle and are forgotten—but the more ventured, the more gained. With so many new operas available, it is increasingly likely that some will begin to appeal to conventional opera audiences, meet high critical expectations, and possibly go on to join the fabled ranks of Porgy and Bess on American opera stages.

Ernest Hilbert with composer Stella Sung before the premiere at the Philips Center for the Performing Arts.

The Red Silk Thread: An Epic Tale of Marco Polo, an opera by Stella Sung after a libretto by Ernest Hilbert

Setting: 13th-Century Imperial China, East China Sea, Persia, and Genoa

Act I

Scene 1: The Grand Throne Room of Kublai Khan

Scene 2: Palace Gardens

Intermission

Act II

Scene 1: At sea on board Khan’s Flagship

Scene 2: Persian Court of King Arghun the Magnificent and Prince Ghazan

Scene 3: A Genoese prison cell and the Gobi Desert

Dramatis Personae

The Venetians

Marco Polo, Venetian merchant traveller, ambassador of the Court of the Khan (tenor)

Maffeo, Marco’s uncle (baritone)

Rustichello da Pisa, author of romances, cellmate of Marco Polo in Genoa (baritone)

The Mongols, Yuan Dynasty

Kublai Khan, ruler of China and Mongol Empire, grandson of Genghis Khan (bass)

Princess Cocachin, seventeen-year-old beauty (soprano)

Khan’s Three Consorts

- Empress Nambui, the eldest (soprano)

- Empress Tegulen, the middle (mezzo soprano or alto)

- Empress Chabi, the youngest (soprano)

Saran, Lady-in-Waiting to Princess Cocachin (mezzo soprano)

Yanira, court astrologer (alto)

Ganbaatar, ship’s captain (baritone)

Ladies and Sentries, Barons and Generals (SATB)

Sailors and Soldiers (tenors and basses)

The Persians, Khwārazm-Shāh Dynasty

Prince Ghazan the Brave, son of King Arghun the Magnificent (tenor)

Caspar, advisor to King Arghun The Magnificent (baritone)

Rostam, King Arghun’s greatest warrior (non-singing part)

Ladies, Attendants, and Warriors (SATB)

Wokou, Japanese Pirates

Genoese Prison Guard (baritone)

Synopsis

The first act begins with the famous Venetian traveler Marco Polo returning to the court of his patron, the Great Kublai Khan, after a diplomatic journey. A lavish celebration is underway (chorus, “Great Khan! Kublai!”). Khan’s daughter, the beautiful young Princess Cocachin, has been promised in marriage to the cruel King Arghun of Persia in order to quell the threat of looming war and reopen the profitable but oftentimes dangerous trade route from Persia to China (“My Empire’s Fate is Found in Love”). Marco Polo and the unhappy teenaged princess find themselves mysteriously drawn to each other (“She is the Jewel of Cathay”). The princess’s lady-in-waiting, Saran, senses trouble and vows to keep the two apart until they leave for Persia. During the celebration, the superstitious Khan’s favorite soothsayer delivers a worrying prophecy about the princess’s future, but the emperor, in a contented mood, chooses to dismiss it (“Good Omens and Prophecies”). During a secret rendezvous the next day in the palace garden, Marco and the princess come to realize that their forbidden love is hazardous not only to themselves but to the future of Great Khan’s empire (“I Have No Fear. Nor Should You”). Marco Polo pledges to set off at once on a new journey and forget the princess forever, but he is waylaid by the emperor, who announces he has chosen Marco Polo, the only man he truly trusts, to escort the princess across perilous seas and deserts to the court of the dreaded King of Persia (“Lead her away / Take her away”).

In the second act, we find Marco Polo in command of a fleet of Imperial War junks carrying the princess to Persia (“Behind us Cathay / Before us Malay”). She has chosen to remain below deck during the passage. Captain Ganbaatar warns of the threat of Wokou, rapacious Japanese pirates, but Marco Polo, preoccupied with thoughts of the princess, ignores the warning. That night, by the light of a full moon, Marco restlessly paces the decks alone. Princess Cocachin, also believing she is alone, emerges from her cabin to sing to the moon (“Safe in the Center of the World”). They meet and wonder why they cannot be together (“Can We Live our Lives as One?”). The princess gives Marco Polo a cloth into which she has woven a red silk thread, promising that, according to a Chinese proverb, whatever happens, the invisible “red thread of fate” will always connect them (“This Silk is White as Mountain Snow”). They are surprised by Saran, who sends the princess back to her cabin. Saran tells the sad story of her own youthful love gone dreadfully wrong (“I Was Young and Knew No Blame”). She explains again why the two must remain apart. After she leaves, Marco Polo sings his own plaintive song to the moon, wondering who he really is after all these years (“Who Am I?”). Before he can finish, alarms are sounded as Wokou swarm the junk. Marco Polo leaps into a ferocious sword battle with the pirates. He must decide if he will risk his life against impossible odds to rescue the princess as pirates carry her back to their ship.

Great Khan surprises his envoy Marco Polo and Marco’s Uncle Maffeo with the prospect of a new expedition.

Years later, we find Marco Polo’s uncle Maffeo arriving before the rest of the expedition in the Persian court only to find it empty. He imagines himself a king for a day, but then begins to suspect that something is amiss after happening upon the Persian King’s attendant Caspar, who frantically prepares for the wedding (“To Rule, to Rule, to Be a King not a Fool”). When Marco and the princess arrive, it is obvious to all that they have grown dangerously close. They are introduced to King Arghun’s dashing and charismatic son Prince Ghazan, who charms the delegation, including the princess. Princess Cocachin trembles at the thought of the impending marriage (“Must I Marry a Man Who is Almost Dead?”), but sudden news arrives that the old King Arghun has died. Marco rejoices only to discover that the wedding will proceed with Prince Ghazan, who by rights will become the new king and bring peace to the warring kingdoms. Marco, jealous and protective, begins to argue with Prince Takesh (“Queen in a Strange and Barren Land?”). Princess Cocachin assumes control over her life for the first time, separating the men and explaining to Marco Polo that their love could never be and that she has decided to fulfill her destiny by marrying the prince and becoming a queen (“We Must Wake to Our Lives”). In the final scene, Marco Polo finds himself a prisoner-of-war in a Genoese prison cell with the writer Rustichello, to whom he relates his wondrous travels, leaving out only the story of his lost love for the princess. Upon being freed from captivity, Marco Polo is given a letter from the Persian court announcing that the princess has been poisoned. The most painful memory of his long life rushes back (“One More Story, Too Hard to Tell”) and Marco finds himself transported to a desert, where he encounters a vision of the princess. Still connected by the red thread, they sing to each other one last time (“We Left Our Homes When We Were Young”).

“All Parts of the East”: An essay on The Red Silk Thread by Ernest Hilbert from the program for the April 2014 premiere.

Ye emperors, kings, dukes, marquises, earls, and knights, and all other people desirous of knowing the diversities of the races of mankind, as well as the diversities of kingdoms, provinces, and regions of all parts of the East, read through this book . . .

Thus begins Marco Polo’s Divasament dou Monde (Description of the World), or, more commonly, his Travels, one of the most famous books of all time. When the world’s greatest traveler set out from his home in Venice in 1271, a “young stripling” aged only 17, Europe had nothing resembling what we know of as opera, which would only emerge around 1600 (Jacopo Peri’s opera Dafne was performed in Florence in 1598, the earliest known opera; the libretto survives, though the music is almost entirely lost), nor could it boast of a civilization as advanced and organized as that of the Chinese kingdoms ruled by the Mongols of the Yuan Dynasty from 1279 until 1360. With his father Niccolo and uncle Maffeo, Marco Polo set out on well-worn trade routes to kingdoms east, most governed by the Mongols in the wake of Genghis Khan’s world conquest. It was an age before modern science cast light across the globe, so we must remember that Marco Polo’s was a world populated by bizarre peoples, traversed by monsters, and lit by the glow of magic. Alongside verifiable descriptions of landscape, Marco Polo regales readers with mythical beasts like the Roc, a bird so enormous it hunted elephants. He was perfectly credulous. Marco Polo experiences no apparent skepticism before the most fantastical, grotesque, and mysterious notions one can imagine. In a very real sense, his world was one perfectly suited to opera.

Opera too is strange. It is magical. It always has been. It creates a universe in which everyone sings all the time, and anything is possible. In his 1781 Prefaces, Biological and Critical, to the Works of the English Poets, Dr. Johnson dubbed it an “exotic and irrational entertainment.” When writing an opera based on a particular historical moment, the imagination is naturally drawn to the grey or dark areas, to things left out, events behind closed doors, so to speak, the intimate connections lost to history. The history of Marco Polo’s stay in the court of Kublai Khan is particularly murky. We are not even certain that he travelled as far as China, and his time there is glossed rather abruptly in the prologue to his Travels. Some historians, like Frances Wood, contend that Marco Polo never actually went to China at all but rather simply recorded stories overheard from fellow travelers or even invented some with the help of the romance writer Rustichello, who served as his amanuensis when the two were held in a Genoese prison during one of the intermittent naval wars between Venice and Genoa (some scholars identify sections they believe were almost certainly later inserted by Rustichello). Others so love the Travels that they will not hear of it being inauthentic. I encounter volumes in which lines such as “This tale may be read as allegory by those who doubt its truth as history” violently scratched out with ink by true believers. Nonetheless, the broad contours of Marco Polo’s travels, his time in China, and return trip, as recounted in his celebrated book, are considered largely historical. Most importantly for The Red Silk Thread, the Travels includes a grueling sea voyage to Persia and from thence overland back to Venice, where Marco Polo arrived with a fortune in jewels sewn into his garments.

Stella Sung and I chose to color the larger shapes provided by the story of Marco Polo’s return journey, introducing perfectly plausible action that is simply impossible to prove or disprove. We teased the mythical from the historical, or, more precisely, from the woolly edges of historical fabric, where it frays and comes loose. Marco Polo has become an icon, a symbol of the distance between Europe and Asia, as well as a merging of dissimilar cultures. Partly because we know so little of him, Marco Polo is usually pictured simply as a great traveler, and this is true, though he was not an explorer or imperialist like later European interlopers. However he was, above all, an Italian businessman. When we read the Travels, we encounter a richly descriptive language devised to match the opulence of the items described. We are treated to pages lavishly packed with goods and treasures. We hear of Baghdadi pearls and cloths of Tabriz gold, sesame oil, lapis, rubies, cotton, flax, hemp, steel, silks, dates, Persian turquoises, thoroughbred horses, Indian coconuts, indigo and ambergris from Zanzibar. These wonderfully exotic catalogs evolved from the mind of a merchant, an enthusiastic and alert trader, what we might call an importer of luxury goods. When describing the bizarre practices of a place, he is sure first to tell us of all the prime opportunities for business to be found there. When he arrives in Charchan, he begins by explaining that “through this province run several large streams, in which also are found chalcedonies and jaspers, which are carried for sale to Cathay, and such is their abundance that they form a considerable article of commerce.”

After he arrives in China, he hardly remarks upon its imperial grandeur, instead taking inventory of potential business possibilities. “Traveling westward three days from the residence of Mangalu, you still find towns and castles, whose inhabitants subsist by commerce and manufactures, and where there is an abundance of silk.” Only later does he get to the “worshippers of idols” who live among tigers, bears, and lynxes. We quickly learn that even in the thirteenth century, business brought the world together, or at least it did for Marco Polo. Stella and I pondered what would happen if a cosmopolitan traveler, what we call a man of the world, accustomed to profitable commercial schemes, were to find himself, at midlife, suddenly yearning for something he absolutely could not have, to go to a place he could not go. Would he risk his own comfort and well-being, possibly his own life, to seize an object of overwhelming desire? And what of a princess daughter of the Great Kublai Khan, sheltered her entire life in a magnificent palace, treated with godlike reverence and guarded as a great prize? How would she feel if she discovered she was to be sent away to marry a strange and frightening monarch in order to finalize one of her father’s treaties? And what would be her reaction to the presence of a charismatic, confident, almost heroic man from another continent, who told pleasing stories of his exploits and discoveries?

The Chinese empire under the Mongols was less insular than it had been or would again become. The Mongols were quick to hire experts from many cultures and religions to work for them, and the simple fact that most of Asia was controlled by relatives of the Khan made travel and trade easy. A young princess of the Yuan dynasty would have met envoys, scientists, and artisans from many places. She would surely have been intrigued by the locales from which they hailed. Perhaps she would have liked to travel to those places herself. We were careful not to envision Marco Polo as a warrior, though he certainly has a cavalier’s swagger and may well have worn a sword. Likewise, we did not want the Princess Cocachin to be merely a demure and submissive maiden. Though we are working with characters that would not be out of place in an opera of past centuries, we wanted the characters to feel entirely modern and to imbue them with fraught emotional states and complex motivations. We feel The Red Silk Thread is a thoroughly contemporary treatment of a distant historical moment, by turns amusing, provocative, and beautiful, a multidimensional tale of duty, love, and destiny, brought to life for the twenty-first century.

2013 Public Workshop performance of Red Silk Thread by the Michigan Opera Studio at the Wallgreen Theater, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

* * *

The Last of Manhattan, an Opera in Two Acts by Daniel Felsenfeld after a libretto by Ernest Hilbert

Setting: Manhattan penthouses, nightclubs, and television studios, all high above street level, in the late summers of 2001 and 2003

Act I

Scene 1: Television Studio, Set of Cy Niceman’s Show, and a Corporate Boardroom

Scene 2: Penthouse of Victoria Towers

Scene 3: The Zoo Ball

Intermission

Act II

Scene 1: The Zoo Ball II

Scene 2: Penthouse at Victoria Towers

Scene 3: After Party Without End at Cameron Twins’ Home

Scene 4: Television Studio, Set of “Entertainment Justice”

Scene 5: Penthouse at Victoria Towers

Dramatis Personae

Circle One

Victoria Wells, Manhattan real estate czarina

Clare Lynott, Victoria’s personal assistant, with a Ph.D. in Philosophy from Columbia

Circle Two

Justine Cameron, rival real estate mogul, eminent upscale dipsomaniac

Renee Cameron, Justine’s younger sister, socialite, occasional memoirist, pop star

Angel Cameron, Renee’s twin, socialite, occasional memoirist, pop star

Tia Crest, Justine’s assistant

Toby Fley, the Camerons’ ghostwriter

Zappo, Renee’s black cat

Zagnut, Angel’s white cat

Zagnut 2, Angel’s replacement cat

Zappo 3, Renee’s replacement cat

Circle Three

Kenneth Sexton, handsome Australian tabloid newspaper magnate

Buddy Sultana, Kenneth’s assistant, all smiles

Wynn Sexton, Kenneth’s younger brother, black sheep, editor of the National Post, a profitable tabloid newspaper

Orson Downe, Englishman, the Sextons’ ghostwriter

Circle Four, Other Denizens of the Island

Cy Niceman, handsome television host; his hair is perfect

Dagman Vermont, Trump-like real estate magnate quickly on the way down, selling off his properties; his hair is not perfect

Fritz and Franz Mazda, brothers, both paparazzi

Yarman Baez, television director

Fresca Verso (dark haired Italian) and Summer Gladly (blonde Californian), glamorous Vanity-Fair-featured actresses, Kenneth Sexton’s dates

Crowd in Times Square during blackout

Assorted contemporary Manhattanites, “hangers on,” sycophants, agents, ex-boyfriends, managers, the like; they are interchangeable Dantean ghosts, banished from reality to drift over the culture with no substance or footing

Various types of the “eternal footman,” elevator operator, beauty consultants, cleaning staff, hairdressers, servants of the court

Although demarked as scenes, these divisions should be understood as tableau vivants, elaborate Boschian extravaganzas, demented fêtes gallants. The scenes are set far above street level and the skyline can always be seen shimmering behind

Offstage choruses made up of various players

* * *

Imagine: Every inch of Manhattan real estate has become a scene of incredible struggle and dispute between two warring firms led by rival czarinas Victoria Wells and Justine Cameron. Even the remaining empty parcels of “air rights” over the rooftops have become concentrated battlegrounds. Beneath the din of ongoing combat, dissolute heirs and their embittered attendants populate a celestial metropolis where every desire is effortlessly fulfilled. Everyone but actual writers has a book deal. Every memoir is a bestseller and every pop single a hit for five seconds, every party merely an opportunity to learn of more parties to come. Competition for popularity and wealth is frenzied and increasingly desperate. Could love of any kind survive in such a ruthless atmosphere, or would those who chose to pursue such things as love eventually be forced out altogether?

Act I

Late summer, 2001: The stage is divided into two separate scenes, chaotic, exuberant displays of commerce and entertainment; the first depicts the Cameron twins on a talk show hosted by Cy Niceman; they promote their new albums and memoirs (“The Active Ingredient is Me”); the second, Victoria and Justine battling in a boardroom over the air rights above the Metropolitan Museum of Art (“My Enemy, You Make Me Smile”). The Cameron sisters each devoted one chapter in their latest memoirs to painting a very grim picture of Victoria as an ugly, bitter, lonely person, and a particular enemy of the Cameron family’s real estate dynasty. They also announce that they are celebrating the release of their new CDs, which feature sadistic songs about Victoria, with a gala costume “Zoo Ball” for the 600 most desirable people in New York. To Victoria’s surprise, her assistant Clare informs her that she managed to secure an invitation to the elite party. Clare, an ambitious woman who has grown bitter in the shadow of Victoria (“Everyone Has a Book But Me”), convinces Victoria to attend in her place, in order to speak with the irresistible Kenneth Sexton, who has recently been named “the year’s hottest man” by Me magazine. Victoria is notoriously celibate and devoted to her business, and Clare knows that placing Victoria into the intoxicating orbit of the alluring Kenneth could well prove her downfall.

Back in her penthouse at Victoria Towers, Victoria complains that Kenneth’s newspapers praise the Cameron sisters while defaming her. She decides to attend the party in order to confront Kenneth. A terraced aria, sung by major characters, outlines the goals and desires of all, inevitably selfish and at cross-purposes (“Nothing Will Be the Same”). Later, at the Zoo Ball, Cy Niceman introduces those entering the party, all attired extravagantly as animals of choice. The excitement dims as attention is focused on the Cameron sisters, who sing their signature duet (“We’re All Happy Now”). Victoria arrives (“Fortune Does Not Hide”). Toby Fley and Orson Downe sing a comic song of the ghostwriters (“We Cook the Books”). The Cameron twins attempt to seduce Kenneth but are unsuccessful. They begin to quarrel. Clare urges Victoria to confront Kenneth. When they begin to converse, Kenneth finds he is strangely and surprisingly drawn to Victoria, as they discover a common enemy in the Cameron twins. Victoria and Kenneth steal away together, to the great irritation of the Cameron sisters, who vow revenge.

Act II

Late summer, 2003: Strangely, the Zoo Ball seems to be happening again, but in an abbreviated form, with entrances and introductions, yet the characters seem a bit stiff. Suddenly a director shouts, “cut!” The party is being reenacted for an E! Network history special, in anticipation of a second Zoo Ball (“No One Knows or Cares / What is Real, What’s Fake”). Victoria, alone in her chambers, awaits Kenneth’s arrival, so they can steal a few moments alone before attending a party that evening, separately (“She Feels Unreal”). Their affair has remained a secret in order to protect both of their reputations. She regretfully expresses her belief that marriage is for those “on the ground,” the “normal” people, not for those in power. But when Kenneth arrives, she finds herself asking him again why they cannot have a “normal” relationship. Using a medieval painting on the wall as an example, he explains that the wealthy and powerful are compelled to surrender some of the freedoms enjoyed by the lowly (High and Low, They’ve Never Met. / It May Change, But it Hasn’t Yet”). He insists that he cannot afford to feel love. She asks why, and he pauses, looks away, and then answers: “You’re just not good-looking enough.” At first, she appears devastated by this, but it then energizes her, as adversity always has. She seizes him and whirls him onto the bed. She straddles him. She tells the story of her rise to power, how she forfeited popularity and beauty (“I Traded Joy for Wealth”). They make love.

At the ball’s after party, the Cameron twins complain of their failure to seduce Kenneth. They have descended into ever more orgiastic pursuits (“The Ball has Ended, and We are All the Same”). A giant black heart shaped bed takes up a third of the room and rotates slowly. It is covered with writhing forms in a limp, doped orgy. It becomes apparent that one of the strangely half dressed people on the bed is none other than the previously unadventurous Clare. She slithers over to the sisters and regales them with stories about Victoria and Kenneth’s secret affair. The Cameron sisters hatch a plot: They will ask Wynn Sexton, Kenneth’s brother and editor of the National Post, to get pictures of Kenneth and Victoria together in order to humiliate Kenneth into leaving Victoria. Justine enters, and her two younger sisters tell her about Kenneth and Victoria. Justine seems saddened and distraught by news of the affair. Her momentary loss of confidence hardens into sheer hatred of Victoria. The two younger sisters now explain their plan to Justine. She dispatches them to fulfill their plot. Clare sings a song of regret stirred by her betrayal of Victoria (“I am a Loser, a Traitor, it is True”), but then tells Justine that she believes Victoria murdered her first husband (“A Little Secret”). They soon learn that Kenneth has gone missing and that Victoria is considered a Person of Interest in the investigation. Justine confesses to Clare that she once had an affair with Kenneth and that Alfred Wells, Victoria’s late husband, was going to leave Victoria for her, just before he disappeared mysteriously (“For Glorious Weeks / We Strolled Small Streets”). The show “Entertainment Justice” carries the now scandalous story of the missing Kenneth and suspected Victoria around the clock.

Victoria is told by her lawyers not to leave her penthouse, and the lobby is under surveillance by the police (“Trapped in the Tower I Made”). Suddenly the citywide blackout of August 2003 descends (chorus, “Nothing Will Belong to You Alone”). By candlelight, Clare attempts to comfort Victoria. Victoria is unmoved by Clare’s appeal. Clare then suggests that the blackout is Victoria’s one chance to slip out of the city, unrecognized, and disappear before the lights come back on (“Time Slips Quickly Away”). Victoria points out that the elevators do not work. Clare tells her that she must descend the darkened stairs as everyone else in the building has and blend into the vast crowd on the streets. Victoria’s candle goes out. Clare, handing her the last candle (“We Must Live Through All We Regret”). Victoria departs.

* * *

“An Otherwise Threatening World: Brief Notes on the Libretto for Daniel Felsenfeld’s The Last of Manhattan” by Ernest Hilbert, from the program for the May 11, 2004 performances

As a librettist, I find myself interested foremost in restoring the notion of the opera libretto as original literary work. Contemporary opera—when not departing from narrative designs altogether, as with Philip Glass’s kaleidoscopic sagas, with libretti by performance artist Robert Wilson consisting of number sequences and found transcriptions—usually relies on demonstrated themes, typically drawn from an existing literary work. Notable exceptions include the operas of John Adams, with libretti by Alice Goodman, which tend to center on modern historical episodes such as Richard Nixon’s visit to China. Recent history has given us the immensely successful Little Women by Mark Adamo and The Handmaid’s Tale by Poul Ruders, with libretto by Paul Bently. Aside from such new operas as the astonishing Ghosts of Versailles by John Corigliano, with libretto by William Hoffman, most operas are literary adaptations (even Hoffman notes that his libretto is “after Beaumarchais”). This is not at all unusual, and adaptation deserves to be considered an art unto itself. Operas in regular repertory tend to derive their themes from stage dramas, novels, and classical or biblical mythology. Only rarely does the dramatic element of opera flow from whole cloth, as one finds with Richard Wagner’s libretti, which he called his “poems,” one component of his far-reaching practice of gesamtkunstwerk, though they owe singular debts to Germanic and Norse mythologies.

The opera libretto makes its home in a world between poetry and drama. Libretto means, literally, “little book” in Italian, and this reflects the reputation and importance it is ordinarily accorded. The most recognizable constellations of the operatic firmament are those of majestic divas and wild-haired composers. Though more distant, and perhaps a bit less distinct, the librettist is nonetheless of great importance. Although many libretti are rather workaday and functional, others stand out as particularly convincing works of art in their own rights (such as W.H. Auden’s devilish libretto to Igor Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress). The successful librettist must make use of the compressed lyrical energy of poetry, particularly in arias and songs, while simultaneously establishing a sequence of dramatic signatures that must, by their nature, bear much more weight than their purely theatrical counterparts. Due to the time constraints presented by musical setting, the plot must be moved forward in a set-piece fashion that contemporary playwrights might find somewhat absurd. As a result, realism has never taken hold in opera as it has in other literary genres.

The opera libretto, like the stage or screenplay, is acutely interdisciplinary. Some dramatists, like Samuel Beckett, attempted to exert an unrealistic standard of control over the production of their works. Wagner solved the problem by placing the entire “music drama” (a term introduced in his 1850 book Oper und Drama and which he preferred to the word “opera”) under his personal control. He is a rare exception. Most opera rises from collaboration. The more famous and fruitful collaborations include those of Richard Strauss and Hugo von Hofmannsthal, and Arthur Sullivan and W.S. Gilbert (in the case of operetta). Even Mozart had his Lorenzo da Ponte, and together they created his three finest operas, Le nozze di Figaro, Don Giovanni, and Così fan tutte. Opera combines literary techniques of accentual-syllabic verse forms, characterization, and plot with sophisticated forms of music, and, as audiences expect, sheer spectacle. Aside from ambitious examples of film-making, opera may be the most extraordinarily interdisciplinary of all art forms. Unfortunately, it is stuck in a museum-like world, held captive by performers and audiences alike, who simply will not allow it the same measures of growth and renewal that other art forms periodically command. One legitimate route toward a partial renovation of the genre—and hardly a radical one at that—is the composition of original libretti written on relevant and persuasive topics rather than adaptations from source works. While adaptations bring a recognizable “commodity” to the work, they also serve to make the literary aspects of the opera undeniably second-hand and subordinate.

After completing our first collaboration, the solo cantata Summer and all it Brings (which was performed in 2002 as part of the Composer’s Collaborative “Non Sequitor Festival,” in 2004 by the New York City Opera at Symphony Space as part of the VOX series, and in 2009 as part of the PEN American Center’s “Elaborations/Collaborations”), Daniel Felsenfeld and I decided to work toward an evening-length companion piece to Henry Purcell’s classic opera Dido and Aeneas. Purcell’s work, based on chapter ten of Virgil’s epic poem The Aenead, has the distinction of being the only English opera written before the twentieth century to be found in regular repertory. It enjoys several other distinctions. Since it is the first full opera written in the English language (early modern), it was a stylistically native creation. Critics of the time did not know what to make of it. Because it was probably intended, in its original form, to be performed by young women, the librettist, Nahum Tate, purged the opera of any bloodshed. A heroic tragedy without carnage certainly made very little sense, then as now. At the opera’s conclusion, Dido simply collapses under the weight of unrequited love and is strewn with rose petals by attendant cherubs. This all contributes to an overwhelming sense of what Felsenfeld has described as a lingering “creepiness” in the opera.

I quickly learned that the “companion” element of the project was of less concern than I had originally expected. I wanted to write a contemporary libretto, for characters in contemporary dress, but with historically universal dilemmas. The Last of Manhattan might be described as a tragic satire. It is written partly in the neglected tradition of laus et vituperatio, simultaneously a condemnation of corruption and a celebration of those courageous enough to resist it. I intended to provide some analysis of power and its uses, the augmentation and abridgement of it through dealings with both allies and enemies. I also wanted to display the power of illusion through mass communication, as well as the undermining effects of traitorous deception within great families. Ultimately, I sought to confirm that the ultimate power may yet reside in the private world of love and its transcendent capacity to transmute and protect us as individuals from an otherwise threatening world.

After James Joyce’s Ulysses transformed the wandering of clever Odysseus into the routine meandering of Leopold Bloom, artists have almost instinctively imagined gods, kings, and heroes as “everyday” people. This is a natural result of the gradual democratization of the arts that has taken place in the past two hundred years. While I applaud this, I felt it simply would not do for my purposes. First of all, it is not very realistic, in my opinion. The world is still populated by incredibly powerful men and women, who do not share the daily grind of their subjects, however much they might pretend to. The characters in The Last of Manhattan breathe in rarefied regions, above the streets, orbiting one another on a plane of power and privilege. At last, the libretto diverged so significantly from its “parent” as to become an adult in its own right, but entirely independent as a result. Those who seek them will find deeply embedded parallels between The Last of Manhattan and both Virgil’s epic and Purcell’s opera, but one need not distinguish them to appreciate this new opera. It stands entirely alone and should not be thought of as an adaptation or modernization at all but instead as an original work of literature devised to accompany an equally original work of music.

* * *

You can listen to Daniel Felsenfeld’s infamous modern cantata trilogy here on WQXR, recorded at the Ferus Festival in the East Village. It begins with “Summer and All it Brings,” which I wrote with Felsenfeld back in 2002. I’m very pleased to be in the company of Wesley Stace and Robert Coover as one of the three librettists for this important sequence. Click through and stream!