“AN EPIC WAH-WAH GUITAR MELTS YOUR GOD-DAMNED FACE OFF AND KILLS POETRY DEAD”

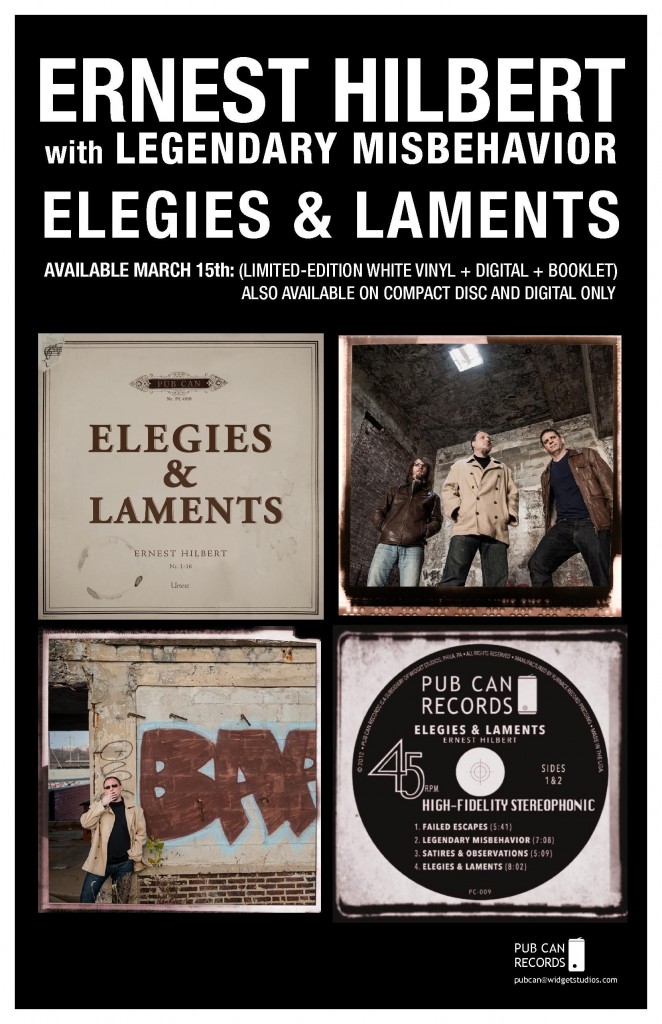

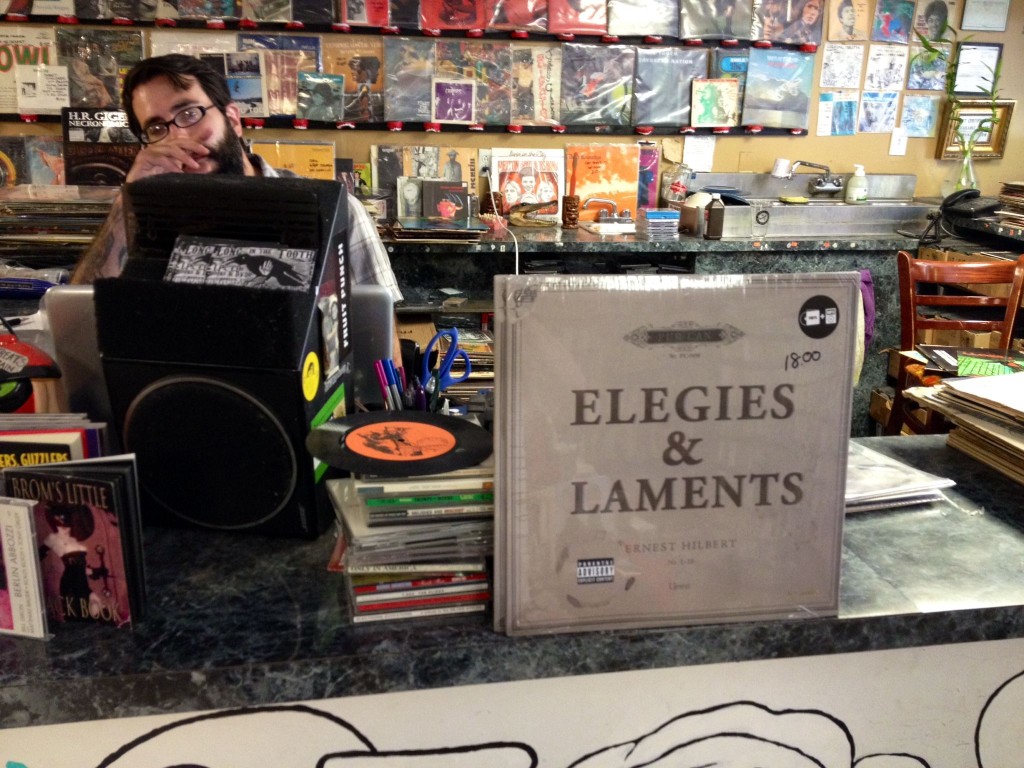

HILBERT, Ernest. Elegies & Laments. Philadelphia: Pub Can Records, 2013. Variety of analog and digital formats.

Ernest Hilbert’s full-length spoken-word album from Pub Can Records.

Order directly from the record label. Also available from Amazon, iTunes, XBox, and BandCamp, as well as streaming from all major services.

Elegies & Laments is a spoken-word album featuring poet Ernest Hilbert reading selections from his book Sixty Sonnets, backed by the rock band Legendary Misbehavior as well as a string orchestra. The album is available for digital download at iTunes, Amazon, and all major platforms, streaming from Spotify and Pandora, compact disc, and in a highly recommended deluxe limited-edition series of 100 numbered copies on 12” 45rpm 180-gram white vinyl in black sleeve and gold-stamp-numbered pictorial jacket with download card and bonus full color audiophile booklet featuring the gear and techniques used in the studio, interviews with the musicians and songwriters, text of the poems, photographs from the studio, and the story of the album, signed by all members of the band. (Several of the white vinyl copies have red vinyl smears and streaks from a White Stripes album pressed immediately before Hilbert’s at the plant.) An additional 100 copies on 180-gram black vinyl will also be issued outside of the limitation in a plain sleeve with no limitation stated on insert. From the record label: “What would it sound like if a book of poetry had its own musical score, like a film, written specifically to match the poems line for line and word for word?

Following the release of his book Sixty Sonnets, poet Ernest Hilbert teamed up with veteran Philadelphia songwriter-musicians Marc Hildenberger and Dave Young to find out. After signing a contract with local label Pub Can Records, the three embarked on a spoken-word project called Elegies & Laments that would eventually grow to include a string orchestra (scored by young composer Christopher LaRosa), a battery of vintage instruments and electronics, mad-scientist rewirings, experimental technologies, session musicians, guest readers, and, perhaps inevitably, a harp. The grape and grain-fueled late night sessions at Widget Studios, on the city’s outskirts, yielded a soundtrack of surprising variety and depth, mingling past and present, making use of indie rock, jazz, heavy metal, classical, and R&B styles. The result is an entirely new kind of spoken word album. Feel the legendary misbehavior, the satires and observations, the failed escapes, the famous elegies and laments of Hilbert’s Sixty Sonnets in a way you have never heard poetry before. Elegies & Laments is essential for anyone interested in the ways poetry and music come together to create a new art form, for aficionados of experimental music to lovers of spoken word.” Literary Magnet hails it as “Amazing and innovative . . . The music is variegated and fascinating, by turns vicious and lovely . . . [it does] what art should do: change things. Elegies and Laments will change you, too.” The album is available for digital download from Apple iTunes, Emusic, Amazon MP3, Last.fm, Spotify, Omnifone, Rdio, Muve Music, Shazam, GreatIndieMusic, MySpace Music, Simfy, Google Music Store, iHeartRadio, Slacker.fm, Rhapsody, MediaNet, Tradebit, 24-7, Bloom.fm, and Xbox Music.

“Amazing and innovative . . . The music is variegated and fascinating, by turns vicious and lovely . . . [it does] what art should do: change things. Elegies & Laments will change you, too.” – Literary Magnet

In Elegies & Laments, the music and poetry work together magically well, miraculously well. It’s a legitimate collaboration. – Best American Poetry Blog

[Elegies & Laments is an] ingenious journey through sense and sound. One of the tracks records a particularly successful open mic where Hilbert reads, followed by stimulating contributions by Quincy R. Lehr, Paul Siegell, and Kristine Young. And introducing each track are tantalizing mashups of recordings, scratchy and haunting, of older poets, from Whitman to Ezra Pound to Sylvia Plath. . . . The poems tend more toward the demotic and streetwise, but never lose Hilbert’s strong imagery, feel for cadence, and rhythmic firmness. A wonderful release. – Synchronized Chaos

There’s a cinematic depth to [Elegies & Laments]. An epic wah-wah guitar melts your god-damned face off and kills poetry dead. There’s too much seething dread and I’m developing an uncomfortable hotness-under-the-collar from the nagging suspicion that I’m being called out for being under-prepared for life, in a way I’m not educated enough to fully understand. Hilbert’s cleverly induced a low-level PTSD with his insidious record. – Raintown Review

An album that defies genre . . . Elegies & Laments . . . is both in-your-face and ethereal. The crowning piece of the album is the last track, “Calavera for a Friend.” Backed by haunting strings, it captures the inevitability of death with heartbreaking candor. Elegies & Laments is an imaginative hybrid that anyone who appreciates poetry and/or music should put their ears to. – PopMatters

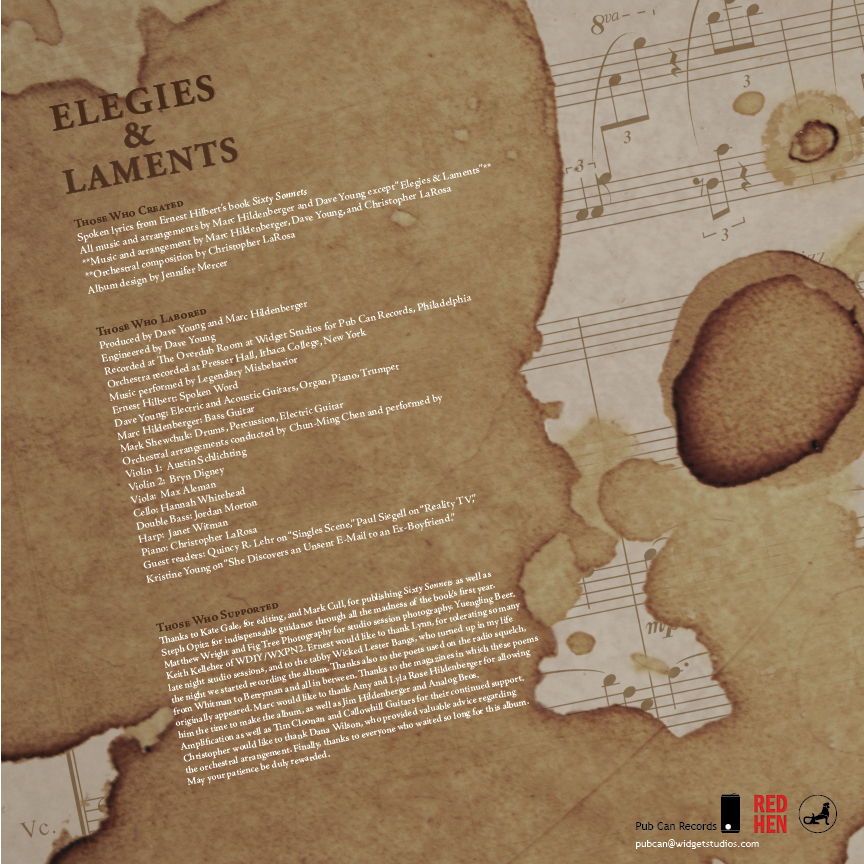

Those Who Created

Spoken lyrics from Ernest Hilbert’s book Sixty Sonnets

All music and arrangements by Marc Hildenberger and Dave Young except “Elegies & Laments”**

**Music and arrangement by Marc Hildenberger, Dave Young and Christopher LaRosa

**Orchestral composition by Christopher LaRosa

Album design by Jennifer Mercer

Those Who Labored

Produced by Dave Young and Marc Hildenberger

Engineered by Dave Young

Recorded at The Overdub Room at Widget Studios for Pub Can Records, Philadelphia

Orchestra recorded at Presser Hall, Ithaca College, New York

Music performed by Legendary Misbehavior

Ernest Hilbert: Spoken Word

Dave Young: Electric and Acoustic Guitars, Organ, Piano, Trumpet

Marc Hildenberger: Bass Guitar

Mark Shewchuk: Drums, Percussion, Electric Guitar

Orchestral arrangements conducted by Chun-Ming Chen and performed by

Violin 1: Austin Schlichting

Violin 2: Bryn Digney

Viola: Max Aleman

Cello: Hannah Whitehead

Double Bass: Jordan Morton

Harp: Janet Witman

Piano: Christopher LaRosa

Guest readers: Quincy R. Lehr on “Singles Scene,” Paul Siegell on “Reality TV,” Kristine Young on “She Discovers an Unsent E-Mail to an Ex-Boyfriend.”

Thanks to Kate Gale, for editing, and Mark Cull, for publishing Sixty Sonnets as well as Steph Opitz for indispensable guidance through all the madness of the book’s first year. Matthew Wright and Fig Tree Photography for studio session photography. Yuengling Beer. Keith Kelleher of WDIY/WXPN2. Ernest would like to thank Lynn, for tolerating so many late night studio sessions, and to the tabby Wicked Lester Bangs, who turned up in my life the night we started recording the album. Thanks also to the poets used on the radio squelch, from Whitman to Berryman and all in between. Thanks to the magazines in which these poems originally appeared. Marc would like to thank Amy and Lyla Rose Hildenberger for allowing him the time to make the album, as well as Jim Hildenberger and Analog Bros. Amplification and Tim Cloonan and Callowhill Guitars for their continued support. Christopher would like to thank Dana Wilson, who provided valuable advice regarding the orchestral arrangement. Finally, thanks to everyone who waited so long for this album. May your patience be duly rewarded.

The Story

What would it sound like if a book of poetry had its own musical score, like a film, written specifically to match the poems line for line and word for word?

Following the release of his book Sixty Sonnets, poet Ernest Hilbert teamed up with veteran Philadelphia songwriter-musicians Marc Hildenberger and Dave Young to find out.

After signing a contract with local label Pub Can Records, the three embarked on a spoken-word project called Elegies & Laments, beginning with recordings of Hilbert reading from his critically-acclaimed book, that would eventually grow to include a string orchestra (scored by young composer Christopher LaRosa), a battery of vintage instruments and electronics, mad-scientist rewirings, experimental technologies, session musicians, guest readers, and, perhaps inevitably, a harp.

The grape and grain-fueled late night sessions at Widget Studios, on the city’s outskirts, yielded a soundtrack of surprising variety and depth, mingling past and present, making use of indie rock, jazz, heavy metal, classical, and R&B styles. The result is an entirely new kind of spoken word album. The Elegies & Laments white vinyl issue was manufactured in Holland and assembled by Furnace Manufacturing, the fabled Virginia firm responsible for collectible vinyl from the likes of Neil Young, Metallica, Black Keys, Bob Dylan, Skrillex, Wilco, Foo Fighters, Tom Petty, Phish, Norah Jones, Nirvana, Mastodon, Bjork, Green Day, Regina Spektor, R.E.M., Lou Reed, Ryan Adams, Band of Horses, and Carole King.

THE MUSICIANS

What attracted you to this project?

Many things, but two stand out as the most significant. First, I knew what a huge challenge a record like this would be, if we were to do it right. Aside from a few random editing exercises in college back in the 1990’s, I hadn’t done anything quite like this before. I knew what it would take, but I also knew that I had no resources to make it happen . . . and that freaked the hell out of me. When something intimidates me, I am struck with an overwhelming desire to overcome it regardless of what it might require. Second, and probably most importantly, I knew that if I were to take on this project, I would have a guaranteed opportunity to get to know and work with some of the most talented and creative people I have ever met and quite possibly ever will.

What challenges does a spoken word album present? How does a project like Elegies & Laments differ from the other albums you have produced?

From a technical point of view, human speech is highly dynamic and full, which makes it hard to blend with other sound sources. That is something I deal with all the time when working on production sound for film and video. It did, however, affect this project in a unique way, because, being a musical album, we sought as close a correlation as possible without removing the focus from the voice. It is a mind-numbing process trying to achieve that balance.

We began the process with nothing but lyrics and a blank musical canvas. We had to create the music for the entire album. That can be very intimidating! Some of the pieces came together quickly, but some took forever. I found myself at times having to carry the entire creative process on my shoulders, while at other times, everyone else was running away with it and I was trying to keep everyone on track. But that is often the role of a producer, and I really enjoy that part of the process.

How did you keep the spoken word vocals so clear over so many instruments?

When I finish an album, I typically mix all of the individual instrument and voice tracks down to a single stereo track for each song and send them to mastering. But in this case, because the voice needed to sit in the music just right, I mixed the music and the voice separately onto two stems so that they could be treated differently during the final master. This allowed me to do things with the music that would have really messed with the voice had we kept it a single track.

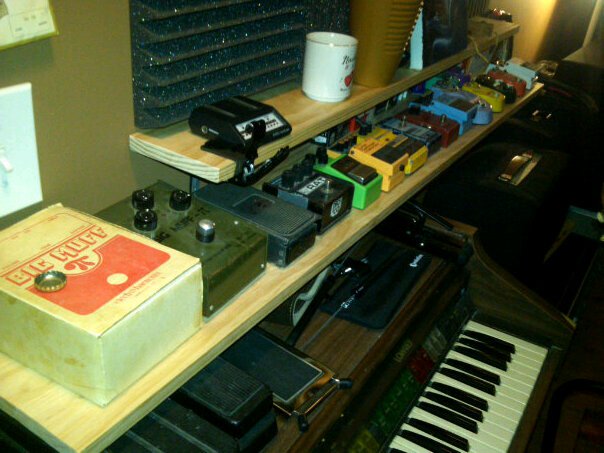

What sort of experimental tools were used for this album?

You know, because we were so cautious not to draw too much of the attention away from the voice track, we really toned down our experimental tendencies. But we did go in with some intense and ambitious notions about what we could achieve. I remember one night, Marc and I had a pretty electrifying session. We must have had ten or fifteen pedals sprawled out on the floor of the studio, all run together, and Marc, with his bass in hand, claiming that he could make any sound effect that I needed. We got lots of interesting sounds that night, but none made it onto the album. Most of the sounds we used on the album came from a Line 6 Bass Pod Pro which helped to get us to the ideas faster. For instance, “Church Street” began with the bass track that has the weird warbling robot modulator thing going on. We just got to that sound and thought, “That’s cool. Let’s try that out.” We have no way of knowing how to reproduce that sound. We also used a number of custom speaker cabinets and a snare drum made from an old tom-tom. Also, we would sometimes use one guitar amplifier for its tone and dynamics, but we’d connect it to the speaker from a different guitar amp for that speaker’s particular sound. Sometimes, I think we do some of this stuff just because we can. Sure, it sounds different, but who knows if it sounds better or if that particular difference is worth the time it took to set up and re-wire. All I know is that I’ll keep doing it, just because I’m curious.

How did you create the poetry-clip radio squelch?

How did you create the poetry-clip radio squelch?

For the poetry clips, we started out by selecting archival recordings of famous poets. We edited the clips down and embedded them into audio I recorded while tuning a transistor radio. I really wanted it to sound like the listener was reaching over and tuning a radio right there in the room. I had another old transistor radio that didn’t work, so I rewired the speaker straight to the earphone jack so it could be connected to any sound source. Then I set it in the studio and put the mic across the room to get a good sense of distance and air. I sent the edits through the headphone amplifier into the studio and into the radio.

Talk about some of the vintage instruments used. Is it true you purchased a particular drum kit for the recording of a single track and then immediately resold it?

Ha! There is a rumor going around that we bought a drum set for one track and then sold it immediately after. It is just a rumor. I think it began because we actually did sell one of the drum sets right after we recorded with it. We actually knew it was going to be sold when we used it. But it was one we had had here at the studio for a very long time and it needed to go.

I love talking about vintage gear. Almost everything on this record is either vintage or is in some way inspired by something vintage. Please, don’t take me the wrong way. I don’t think that something has to be vintage in order to sound good. I just believe, wholeheartedly, that there was a time in the short history of popular music when some of the best things were going on all over, and, if the gear had something to do with it, why not at least start with that same foundation?

I think the most unique or interesting piece is the Lowrey Magic Genie organ used in the first and second sections, “Failed Escapes” and “Legendary Misbehavior.” You know, Garth Hudson of The Band played a Lowrey. My buddy called me up one day and said, “Grab your car and come over. There’s an organ out on the curb that you’ve got to check out.” Not knowing what it was, but also being highly aware that there was a Hammond organ repair shop across the street, I didn’t hesitate for a moment. We had to fight off the trash men, who had just shown up, but we finally got to it and muscled it into the car. When I got it back to the studio, I found that a few of the keys didn’t work, but you could still get some interesting sounds out of it.

This album, a soundtrack to a book, had its genesis with you. It really is your brainchild. Can you say a few words about how it all began?

Actually, it all began years ago while Hilbert and I were undergraduates. I am pretty sure we were at my father’s house in New Jersey, maybe writing a paper together or studying for an exam. Hilbert was already writing very good verse (maybe a touch too scholarly), and I was playing in a few serious bands. We wanted to do a project together and I said we should do a spoken word album, but unlike one anyone had done before: no contrived funk grooves vamping under someone reading poetry. My brother and I were getting into recording and sampling different sounds and noises, and I had just started playing around with experimental sounds using strings of effects pedals and a bass guitar only. Needless to say, the project never got off the ground. Fast-forward to about four years ago. Hilbert and I were sitting in Tria, on 18th Street here in Philadelphia, talking about the release of his first book, and I casually said we should do a “soundtrack to the book.” I think he liked the phrase as much or more than the idea itself. I felt an immediate regret for my wine-fueled idea, as I knew there was no way I was getting out of it this time. By the end of the night and quite a bit more wine Hilbert had indeed convinced me to take on the project. I had just left a group called The GreyJacks but had built a lasting friendship/musical partnership with the guitarist Dave Young. After a phone call the next day, and a meeting soon after, the project was on.

You have considerable experience not only playing with bands but also with spoken word artists. How did your time backing spoken word performers influence the way you approached this album?

I had been part of a scene in the early 1990’s playing open-mic nights at the Middle East Restaurant, Silk City Lounge, and a few other places around Philadelphia where a group of improvising musicians would back spoken-word poets. It was actually really fun, but I knew it was not at all the way I wanted to go with this project. From the first moment in the bar I knew I wanted to write music like a movie soundtrack, music that didn’t just exist along with the spoken word—and certainly nothing that competed for attention with it—but music that could add an extra dimension to the poetry. I have always loved the way the music and imagery work together in a really good film soundtrack, and that is what I hoped to achieve with this project. I wanted to think about the meanings, imagery, and implied emotions of each poem and try to bring them out with the music. The music was never meant to be thought of as individual songs. They are there to enhance the words.

Did you face any particular challenges in writing and recording a spoken word album that you had not encountered in your work with bands?

I had a number of challenges. When I work with bands, singer-songwriters, or other musicians everyone is thinking in terms of a song, i.e. meter, tempo, harmony, and melody. When I sat down to begin working with the recorded poems none of that existed or was even implied. Obviously, when reading their own poetry poets have no need to stay in time. Finding a tempo and then being able to flow with the changes in tempo were a challenge. Luckily, we had the perfect drummer for the project in Mark Shewchuk. He is probably the most sensitive drummer I have ever had the pleasure of playing with, not to mention one hell of a guitar player. His parts almost make no sense when soloed, but when the rest of the band is brought back into the mix it’s magic. He was really the secret weapon on this project. Well, along with Chris LaRosa of course, an incredibly talented young composer who scored the final section. He took a rudimentary idea I had come up with and turned it into the most extraordinary piece of music. I couldn’t be more honored that he worked with us.

In addition to writing the music for the album with Dave Young, you played all bass parts. You created some remarkable sounds. What techniques did you employ to achieve these?

Most of the things that made it onto the finished album were fairly standard. I always play 4-string electric bass. I played finger-style, palm-mute, picked, some chords and double stops, harmonics, and a bunch of effected bass. Most of the album is just good old fashion bass playing. A few pieces have effects. One of the pieces has about eight layers of bass and nine or ten layers of guitars. Dave would know exactly. We created a bass and guitar chorus by harmonizing with ourselves on multiple tracks using slightly different sounds. I think the good thing is it doesn’t sound too tweaked. Dave mixed it in a way that you really can’t tell exactly what is going on. It is just a bunch of cool sounds. I certainly never had any intention of making some kind of “bass show-off” album. I am only interested in these sounds and techniques for what they can do for the music.

I understand there were experimental sessions before the album was recorded. Can you describe one of these sessions?

I had hoped to incorporate some experimental sound ideas I had. Dave and I spent a night with my basses and about fifteen effects pedals creating sounds I wanted to use as layers throughout the album. I don’t think Dave quite followed my vision and the night quickly became tedious for him. Somewhere we have a couple hours of really unusual sounds. We recently found them and listened for a while. There was actually some really cool stuff we captured. We had actually forgotten about it all together . . . or in Dave’s case maybe blocked it out!

On the track “Church Street,” there seem to be an enormous number of lines in the bass and guitar chorus. What are you doing there?

“Church Street” is a bass and guitar chorus that Dave and I devised. There are eight layers of bass and nine of guitar. The first bass part was performed with a ring modulation effect [a ring modulator frequency-mixes or heterodynes two waveforms, and outputs the sum and difference of the frequencies present in each waveform. It produces a signal rich in partials, suitable for producing bell-like or otherwise metallic sounds] which can be a bit unpredictable. It set the tone for the layers we would put on afterwards. I used something called Maleko Industries Barker Assmaster (that’s right!), a wacky distortion pedal based on the original Maestro Brassmaster, which supposedly simulated a brass section. I harmonized with myself, changing the tone and picking techniques with each pass.

You used some custom bass guitars on the album. What were they?

I used three main basses on the album. The Dark Marc is a bass I developed about ten years ago. I have always been into modified instruments. I got it from my brother Jim, owner of Analog Bros. Custom Amps. He is an electrical engineer extraordinaire and evil-genius mad scientist. We have never been able to leave well-enough alone. That constant tinkering led to me to assemble basses from various sources, Frankenstein-style. The Dark Marc was built around a pair of Dark Star pickups. They are modern remakes of the original pickups that Hagstrom made for the Guild Starfire bass in the 1960’s, the bass that Jack Casidy of the Jefferson Airplane made famous. A guy named Fred Hammon reverse-engineered them and started building them by hand with top-notch parts. They are huge single coil pickups with an amazing sound. Unfortunately, Fred has quite literally disappeared from the music scene. No one has heard anything from him in some time. The rest of the bass is made up of a black korina wood body, a maple neck with ebony fret board, and hipshot hardware. It is a passive bass strung with Labella Flatwounds. Everything is put together to bring out the deep fundamental tones of the pickups. Another I used is the Callowhill j(unk). My good friend Tim Cloonan at Callowhill guitars built my dream bass last year. A perfect Jazz. Light, balanced, even, with no dead spots, impeccably crafted. I was able to go into the shop and handpick the woods: Alder for the body, maple for the neck, rosewood for the fingerboard. It has a pair of Nordstrand humbucking J pickups and a Sadowski preamp. Since I play in passive mode most of the time I asked Tim to wire it with a push-pull volume knob. When the knob is down, the bass is passive, and I it pull up to engage the pre-amp. Amazing bass. A third I used is the Callowhill Infini “Thaddeus Tribbet” Signature model, the bass Tim designed with Gospel great Thaddeus Tribbet. I believe this was the actual prototype. Tim lets me take basses home from the shop to play for a while and give my opinion (I think he is just humoring me as his clients are some of the best players on the planet, such as Owen Biddle, Tim Lefebvre, and Derrick Hodge). When I took this bass home I just couldn’t give it back. Everything I played on it sounded great, and that is saying something. Others that may be on the record (we didn’t keep very good notes) include my first love, a 1971 Fender Precision, a Marleaux J (beautiful handmade bass from Germany), and The Analog Bass #1 (A Fender-Style P/J bass my Brother and I put together).

Mark Shewchuk

You played drums on Elegies & Laments. Had you worked on a spoken word project before?

In the early-mid 1990s, I spent an afternoon with an extremely creative friend of mine making short cassette 4-track pieces based upon his readings. I think we free-styled it live. I played a Fender Rhodes electric piano and overdubbed the percussion. He also played clarinet. It was rough and seat-of-the-pants project, but it ended up hitting the spot.

Working on this project was a beautiful opportunity. The level of focus, dedication to craft, and vision of the piece were enticing and contagious. Without any help, Hilbert’s material and flow stands up by its own damn self, and it is a new animal altogether when supported by the production talents of Dave Young. The quality of the participants and the collective goal influenced me to put my best into the effort.

How did you come up with the beats for songs like “Domestic Situation”?

I never played a note on any of the tracks, drums or guitar, without direction from Dave Young. It’s hard to remember specifically, but I’m sure he encouraged me to follow Hilbert’s vocal track and Marc’s bass while attempting to add an element of insecurity, rhythmically speaking. I do remember that the take we ended up using was the first one, which Dave Young initially called “too quirky!”

What [brand] drums did you play?

I used my cheapo Mapex small jazz drums for the initial sessions as they were the only ones I owned at the time. After thirty years of drumming, I got the Pearl Masters Premium thin-shelled maple drums with old Ludwig style tone rings as my first “big boy” drums. I chose these for vintage construction and tone in a modern high-end drum. 20×16” bass drum, 12×9” tom, 14×14” floor tom.

Christopher LaRosa

How did you come to be involved in the Elegies & Laments project?

I had already collaborated with producer Dave Young on a few projects prior to Elegies & Laments. We met up on a cold January night in 2010 when I was home from college for winter break. He described a new project he was working on with a poet and asked if I had any interest in writing a piece for the album. When I read the poems, I immediately jumped on board.

Since I was still working toward my undergraduate degree, I had to work on the project from Ithaca, New York. Young, Hilbert, and I relied mainly on electronic correspondences to communicate about the piece. I did not see Young again after that initial meeting until the recording session with the orchestra a few months later, and I did not meet Hilbert in person until about a year later! Because I had spent so much time with his poetry and he with my music, it seemed like we already knew each other when we finally met.

What particular traditions or influences did you draw upon when scoring the last section of the album?

What particular traditions or influences did you draw upon when scoring the last section of the album?

One of the main challenges I faced in writing Elegies & Laments was justifying an orchestral piece on an otherwise rhythm-section driven album. Still, the poems’ wide emotional spectrum seemed to require the richer palette of an orchestra. In order to coalesce the two divergent ensembles, I drew from the rest of the album’s style and began “Elegies & Laments” with a bass line established by Marc Hildenberger. A good portion of the piece’s thematic material comes from this rhythm-section-inspired kernel.

Since the poetry struck me as distinctly American, I drew upon the mid-20th-century American art music tradition. The expansive quality of “Calavera for a Friend” is certainly reminiscent of Aaron Copland. Minimalism, a style fairly unique to America, also influenced the piece to a lesser extent.

The “Elegies & Laments” sequence, the last quarter of the album, was performed in concert at Ithaca College in April 2012. What was the audience response?

The audience greeted the piece with great enthusiasm. Audience members praised the poetry’s descriptive precision and far-reaching themes, the music’s cinematic quality, and the drama created by the integration of the two. It was a true pleasure for me to lead the dedicated orchestra with Ned Donovan, who eloquently delivered the poetry with vigor, tenderness, and sincerity.

You used some very specific thematic techniques when scoring the last section of the album. Can you give us a few details?

You used some very specific thematic techniques when scoring the last section of the album. Can you give us a few details?

The music had to play an interesting function in relation to the poetry. In one sense, I approached “Elegies & Laments” as a film-score, requiring precisely timed musical events that enhanced but did not overwhelm the poetry’s drama. Simultaneously, I approached the piece as an art song. The themes and instrumental techniques had to reflect the context and tone of the poetry and color the carefully chosen words. The last three poems provide excellent examples of this text painting.

In “Biglin Brothers Racing,” the viola and cello sections play long cyclical melodic lines that depict the regularity, cooperation, and strength of the rowing. The rhythmic fluidity of the lines traces the oars’ path through the water and air. Meanwhile, the piano’s gentle ostinato creates the aural image of water quietly lapping against the boat.

The discordant tone of “The Ancient Sailor Leaves his Heartless Patrician Lover to her Lyre” suggests greater harmonic tension. The strings play with their bows closer to the bridge, creating an edgy, almost metallic timbre. On top of the strings’ cresting waves, the speaker’s “notes cut onto frost-flashed staves” become more and more persistent in the harp.

In “Calavera for a Friend,” the violins sound long tones in the uppermost register while the basses sound their lowest notes. The extreme registers suggest the expansive quality of life, while the empty middle register the violins and basses frame contribute to the hollow feeling death brings. The low strings and high strings slowly move toward one another, coming into focus as the poem illuminates the true ramifications of death. As the deceased’s ties to the world are broken, the string players slowly drop out. Since “some small items might remain,” the large string ensemble ultimately diminishes to a trio.

Ernest Hilbert

What was it like working as a poet in a recording studio?

Dave Young is a superb producer. He is tolerant, to a point, but he always maintains complete control and is an unwavering perfectionist. He thinks for a few moments before responding to any question that matters. He is profoundly serious—though not lacking a sense of humor—and that is precisely the kind of director a project like this needs. The first night I came to the studio he asked me to read “On the Twenty-Fifth Anniversary of John Lennon’s Murder” nearly eighty times. He discarded every one. On my next visit, he finally got a take he liked, but when Marc Hildenberger came in and heard it he wanted it done again. We met halfway. Dave punched in a new reading of the closing couplet. I knew I was in for a real workout. Both Dave and Marc are pros in the studio. They have acquired a level of patience that is beyond anything I can imagine. I am a poet, not a studio guy, so I like to get in and out as quickly as possible. They can work for hours and days on end. I didn’t meet Mark Shewchuk until after he had recorded the drum tracks. He’s fabulous on the drums, and he also played the guitar solo on the climactic ending of the “Legendary Misbehavior” section of the album. He brought a lot to the record. I can’t imagine a better drummer for this project.

What do you think Dave and Marc each brought to the record?

What do you think Dave and Marc each brought to the record?

Dave has more of a pop sensibility, and, as I mentioned, is a perfectionist on the technical level. He has an incredible ear and boundless energy. He fronted a band called The Internationals, and their single was “Celebrity Rock Star,” with Dave’s high school year book picture on the cover enclosed in a lipstick heart. That says it all. He can deliver a polished, perfect pop or rock song. Most of the artists on the label are singer-songwriters with traditional styles. Marc, on the other hand, provides a darker, more experimental element to the album. He is Dark Marc, after all. He competes in Iron Man competitions and knows more about fine wines than most sommeliers in the country. In short, he’s an action movie super villain. Think about it. Dave and Marc are a great match both as musicians and songwriters. Only Dave can successfully reign-in and channel Marc’s experimental techniques and tempestuous emotional drives, and Marc’s wilder tendencies spark similar creative impulses for Dave.

How about Christopher LaRosa?

I’m convinced that LaRosa is a prodigy. He was only about twenty years old when he worked on the album. I provided lyrics for a segment of his “Vignettes of Two Lovers” sequence, and he in turn composed the music for the tail-end of the album Elegies & Laments, which, up to that point, is more of a rock album. He is extraordinarily gifted, and I’ve admired all of his recordings. We are very lucky to have had him on board. The album wouldn’t be what it is without him.

How about the guest readers?

I first learned about Paul Siegell in an issue of Paste magazine. It’s primarily a music magazine, but they did a profile of him as a poet because his principal inspirations are musical. After seeing him in the magazine, I set out to locate him and forge an alliance of some sort. We met up and drank beer at the Good Dog and later that night closed Oscar’s Tavern over on Sansom Street. We became fast friends, and I read with him not long after at the Highwire Gallery during a hurricane. We performed between performances by a noise band that was just back in town after a European tour. I felt he’d be a good candidate to read “Reality TV” for the album. He nailed it, but a year later Dave brought him back in to rerecord it because the musical lines written around it demanded a slightly different rhythm. Quincy R. Lehr is a satirical poet from New York City, a true dandy and rock star in his own right as bass player for the post-punk band Black Statues. I brought him in to read “Singles Scene” because he has a sardonic, European approach that suits the dreamy humor of that poem. Kristine Young is Dave’s wife. We wanted a woman to read “She Discovers an Unsent E-Mail to an Ex-Boyfriend,” and one night we decided to record a scratch track to work the music around. Kristine did it as a favor to us because she happened to be in the studio that night, but it turned out to be a fit. She sounds utterly nonchalant, a bit bored, only very slightly repentant, but not much. It really works well.

You refer to the band as Legendary Misbehavior.

Yes, they are a studio band, though there will likely be attempts to reproduce parts of the album live on stage. The band, such as it is, really consists of Dave, Marc, and Mark, though many more musicians performed on the album. For a live performance we would likely dragoon another four or five musicians. There is a long tradition of studio bands. For instance, “Beware the Blob,” the theme song that Burt Bacharach and Mack David wrote for the classic Steve McQueen sci-fi/horror film The Blob, was performed by a group created for the occasion called The Five Blobs. They were studio musicians, and singer Bernie Knee layered his own voice. It was released by Columbia Records and actually hit 33 on the Billboard Hot 100! Legendary Misbehavior is my own version of a purpose-built band.

Why this album, and why now?

After my book Sixty Sonnets came out, I spent a few years touring around and reading from it in London, New York, Los Angeles, Boston, all around. Some of the poems, like “Prophetic Outlook” and “Calavera for a Friend,” are standard repertoire for my live readings. I usually start with the first and end with the second. “Prophetic Outlook” is a deeply cynical poem, which burlesques the attitudes it pretends to promote. Like many of my poems, it relies heavily on several kinds of irony. A poem like “Calavera for a Friend” is strictly elegiac, though it rises from a satirical tradition. I used to joke to promoters that I was going to turn up with my own band. When I reconnected with Marc, and we discussed our old idea, it just roared to life. The project became ever more ambitious, perhaps to match the egos of all involved, and before I knew it we had orchestras and horns, harps and special effects. It was impressive but also somewhat frightening. For a while it seemed we may have reared a beast that was beyond our ability to control. At times I despaired that it might never be done. Luckily, after much wrestling with raw material and many battles of wills, the album was completed. Its release is timed with the publication of my new book, All of You on the Good Earth, which is a sequel to Sixty Sonnets. I believe this album stands alone and also works as a companion to the books. There is nothing quite like it. One might say it is all the world needs of such things.

Is there a hidden track?

No comment.

THE GEAR

Drums: Mapex jazz drum kit with 18” bass drum (no hole), 1966 Ludwig Supraphonic 400 snare drum, Early 1960’s Zildjian cymbals: 14” hi hats, 18” crash, 20” ride.

Guitars: Yamaha classical guitar, Ibanez Artcore 2002 AFS 75T with DeArmond pickups, Fender Blues Deville (tweed), 1986 Fender Jaguar ‘65 Reissue (made in Japan) with Seymour Duncan Antiquity II “Jet” pickups, Fender ‘65 Deluxe Reverb reissue amplifier.

Bass: DarkMarc Custom 4-String with Dark Star pickups and La Bella flatwound strings, Line 6 Bass Pod Pro (rack mount).

Organ: 1960’s Lowrey Magic Genie.

Trumpet: Yamaha YTR3320 trumpet.

Part Two: “Legendary Misbehavior”

Part Two: “Legendary Misbehavior”

Drums: Gretsch Catalina Club jazz drum kit with 18” bass drum, 1980’s Remo Quadura drum kit with power toms and 22” bass drum, Ludwig Rockers snare drum, early 1960’s Zildjian cymbals 18” crash, 13” New Beat hi hats, 22” Zildjian K Constantinople Thin Overhammered ride cymbal.

Guitars (Dave): Gibson SG Special 1991, Fender “Nashville” Telecaster (made in Mexico), Sovtek head amplifier, 1965 Fender Vibro-Champ amplifier, 60’s FBT bass speaker cabinet with 2 Carvin British 12” speakers, Custom Leslie-style Rotating Speaker Cabinet, Pro Co Rat distortion pedal, Native Instruments Guitar Rig software, (sample: Marshall Plexi with 4×12” speaker cabinet).

Guitars (Mark): Gibson Les Paul Standard 2006 with Seymour Duncan Antiquities Humbucker pickups, Fender ‘65 Deluxe Reverb reissue amplifier, Pro Co Rat distortion pedal, Ibanez TS9 Tube Screamer pedal, Dunlop Crybaby wah pedal.

Bass: DarkMarc Custom with La Bella flatwound strings, Callowhill Guitars J(unk) DarkMarc Model with DR Lo-rider strings, Callowhill Guitars Infini Thaddeus Tribbett Signature with Thomastik flatwound strings, Maleko B:assmaster pedal, Line 6 Bass Pod Pro (rack mount).

Organ: 1960’s Lowrey Magic Genie.

Part Three: “Satires & Observations”

Part Three: “Satires & Observations”

Drums: Mapex Jazz drum kit with 18” bass drum (no hole), 1966 Ludwig Supraphonic 400 snare drum, Early 1960’s Zildjian cymbals: 14” hi hats, 18” crash, 20” ride (with sizzle chain).

Guitars: Ibanez Artcore 2002 AFS 75T with DeArmond pickups, Fender Blues Deville (tweed), Fender “Nashville” Telecaster (made in Mexico), 1965 Fender Vibro-Champ amplifier.

Bass: DarkMarc Custom with La Bella flatwound strings, Callowhill Guitars J(unk) DarkMarc Model with DR Lo-rider strings, Callowhill Guitars Infini Thaddeus Tribbet Signature with Thomastik flatwound strings, Line 6 Bass Pod Pro (rack mount).

Piano: M-Audio Keystation Pro 88 MIDI controller, Native Instruments Akoustik Piano software (sample: Steinway Concert D Grand).

Part Four: “Elegies & Laments”

Part Four: “Elegies & Laments”

Snare Drum: Custom converted 13” x 9” tom (1950’s or 60’s).

Bass Guitar: 1970’s Harmony Marquis (EBO-style) bass guitar with La Bella flatwound strings, Line 6 Bass Pod Pro (rack mount).

String Orchestra (10 takes overlaid): contrabass, cello, viola, and two violins.

Piano: Steinway Concert Grand Model D.

Harp: Lyon and Healy Style 17 Semi Grand.

The Words

The spoken work on the album consists of sixteen poems selected by Dave Young from Ernest Hilbert’s critically-acclaimed book Sixty Sonnets and read by the author.

Notes on the Poems

The four sections of the album Elegies & Laments correspond to four of the seven chapters in the book Sixty Sonnets. The sixteen that became songs were selected by Dave Young.

Part One: “On the Twenty-fifth Anniversary of John Lennon’s Murder” and “Corned Beef Hash and Two Eggs over Easy, Coffee” are loosely based on real events that took place in New York City near the date indicated. The two poems appeared together in the Cimarron Review. The noir fantasies of “She Remembers How They Fled from the Liquor Store Robbery in New Mexico” and “The Fugitive Spends Christmas in a Las Cruces Motel Room” were composed during an otherwise uneventful period spent in New Mexico, inspired as much by the landscape as the imagined story. No magazine found them fit to print.

Part One: “On the Twenty-fifth Anniversary of John Lennon’s Murder” and “Corned Beef Hash and Two Eggs over Easy, Coffee” are loosely based on real events that took place in New York City near the date indicated. The two poems appeared together in the Cimarron Review. The noir fantasies of “She Remembers How They Fled from the Liquor Store Robbery in New Mexico” and “The Fugitive Spends Christmas in a Las Cruces Motel Room” were composed during an otherwise uneventful period spent in New Mexico, inspired as much by the landscape as the imagined story. No magazine found them fit to print.

Part Two: “Church Street” first appeared in Perihelion and is dedicated to Daniel Nester. The street is located in the town of Mount Holly, New Jersey. “A Sad Last Number for the Gentlemen at the Tavern” also appeared in Perihelion. “Domestic Situation” first appeared in American Poetry Review and later on the websites of The Poetry Foundation, Best American Poetry, and the National Endowment for the Arts program Poetry Out Loud. It is an entirely invented scenario that did not “really happen” despite the poem’s own claims, though the abuse, anguish, frustration, and bad decisions made by the central character in her relationship with a demon lover will be familiar in many forms the world over. It is intended more than anything as a simple provocation and an attempt to show that all things—including forgiveness, trust, and love—can be taken too far. The record studio in “Blotter” was that of Conscience Records on 14th Street and 11th Avenue in the meatpacking district of lower Manhattan. After MTV studios bought out the entire floor of the building, several fellow degenerates invited me over to send the remains of Conscience off with a bang. I don’t remember who brought the nail gun. The bar from which the coffin was removed was Bellevue Bar, now shuttered, in Hell’s Kitchen on the ass-end of Port Authority bus terminal. It was the site of much madness and depravity. The police successfully evaded early in the poem were the Cherry Hill Police. Those unsuccessfully evaded were the Hainsport Township police. The poem first appeared in Daniel Nester’s infamous Unpleasant Event Schedule.

Part Three: Prophetic Outlook,” which debuted in American Poetry Review, is intended as a mockery of those with bad outlooks, but the dire economic state into which the poem was launched seems to confuse the joke a bit. Although I have no knowledge of family teams actually eating worms for the entertainment of other families at home, as portrayed in “Reality TV,” I suspect that it may have happened, though I can attest that an instance of contestants eating worms once caused me to turn my television off, very nearly for good. No magazine editor could stomach the poem, and its first public appearance was in the book itself. “The Singles Scene,” which readers first encountered in the now-defunct newspaper the New York Sun, was inspired in part by my own lovely wife Lynn, who really did have incomplete sets of dolls as a girl, though it must be said that this was no predictor of her own future inability to form steady, lasting, and supernaturally patient bonds. “She Discovers an Unsent E-Mail to an Ex-Boyfriend” is not based on anyone in particular, but the circumstance will not appear alien to most women. It is the one poem on the album that I really felt had to be read by a woman (two other poems on the album are written from the perspective a woman but read by me).

Part Three: Prophetic Outlook,” which debuted in American Poetry Review, is intended as a mockery of those with bad outlooks, but the dire economic state into which the poem was launched seems to confuse the joke a bit. Although I have no knowledge of family teams actually eating worms for the entertainment of other families at home, as portrayed in “Reality TV,” I suspect that it may have happened, though I can attest that an instance of contestants eating worms once caused me to turn my television off, very nearly for good. No magazine editor could stomach the poem, and its first public appearance was in the book itself. “The Singles Scene,” which readers first encountered in the now-defunct newspaper the New York Sun, was inspired in part by my own lovely wife Lynn, who really did have incomplete sets of dolls as a girl, though it must be said that this was no predictor of her own future inability to form steady, lasting, and supernaturally patient bonds. “She Discovers an Unsent E-Mail to an Ex-Boyfriend” is not based on anyone in particular, but the circumstance will not appear alien to most women. It is the one poem on the album that I really felt had to be read by a woman (two other poems on the album are written from the perspective a woman but read by me).

Part Four: “At the Grave of Thomas Eakins, Late Winter” is set in the Woodlands historic cemetery in West Philadelphia near our home. Among Eakins’ most famous paintings are those of the champion rower Biglin brothers, James and Bernard, and the controversial large work known as “The Gross Clinic.” Dr. Gross is interred in the same cemetery not far from Eakins. “The Biglin Brothers Racing” was painted in 1872 and became a United States postage stamp in 1967. The brothers rowed on the Schuylkill River, which is easily glimpsed from the vantage of the Woodlands. “The Ancient Sailor Leaves his Heartless Patrician Lover to Her Lyre” was envisioned as a kind of ageless nightmare and owes nothing to any particular example. “Calavera” means “skull” in Spanish and refers to “calaveras literarias,” satirical poems written for the annual Day of the Dead celebrations, in which one humorously imagines a friend or public figure dead. “Calaveras de azúcar” are small candy skulls placed on altars and sometimes eaten in a symbolic gesture of consuming death itself. “Calavera for a Friend” first appeared in the pages of The New Republic.

This album is performed and recorded in memory of Bill Drourr, who loved rock ‘n’ roll.

Now pour a drink, and turn this album up. Loud.

This is number __ of 100 only copies signed by all members.