Ernest Hilbert is a poet, librettist, critic, and rare book dealer resident in Philadelphia. His debut poetry collection Sixty Sonnets (2009) was described by X. J. Kennedy as “maybe the most arresting sequence we have had since John Berryman checked out of America.” His second collection, All of You on the Good Earth (2013), has been hailed as a “wonder of a book,” “original and essential,” an example of “sheer mastery of poetic form,” containing “some of the most elegant poems in American literature since the loss of Anthony Hecht.” His third collection, Caligulan (2015), has been called “brutal yet beautiful,” defined by “pleasure, clarity, and discipline,” “tough-minded and precise,” filled with a “stern, witty, and often poignant music,” “a page-turner in a way most poetry books can never be,” and “an honest book for dishonest times.” Caligulan was selected as the winner of the 2017 Poets’ Prize. His fourth collection, Last One Out (2019), has been described as “a book haunted by loss,” “elegant and athletic, eloquent and brave, deeply thought and felt,” “human and moving.” Ilya Kaminsky declared that “Last One Out is a very beautiful book . . . it sings.” A. E. Stallings wrote of the book that “a certain amount of youthful edge and swagger has been worn away, but is replaced by mastery, depth, and mellowed sweetness.” His fifth book, Storm Swimmer, was selected by Rowan Ricardo Phillips as winner of the 2022 Vassar Miller Prize and appeared in 2023. Phillips described the book as “a gleaming cornucopia of dreams, nightmares, tenderness, and grace . . . a rare book, both willing and able to capture the wide and relentless range of the human condition in its varying lights and shadows, and in settings spanning the mundane, the tawdry, and the sublime.” The Hudson Review declared it “a book of excellent poems,” naming Hilbert “one of his generation’s most interesting poets.” The Washington Post Book Club described it as a book of “harrowing action” in which the “undeniable delicacy of human life [is] set against the beautiful chaos of nature.”

Hilbert’s poems have appeared in Yale Review, American Poetry Review, Harvard Review, Parnassus, Sewanee Review, Hudson Review, Boston Review, Verse, The New Criterion, Seneca Review, The New Republic, American Scholar, Oxonian Review, and the London Review, as well as several anthologies, including Best American Poetry (2018), the Swallow Anthology of New American Poets (2009), Two Weeks: A Digital Anthology of Contemporary Poetry (2011), The Incredible Sestina Anthology (2013), and two Penguin anthologies, Poetry: A Pocket Anthology and Literature: A Pocket Anthology (2011). Hilbert has written about books for the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, the Spectator, Fine Books & Collections, and The Hopkins Review. He has published essays about breaking a rib in a mosh pit during a Slayer concert, the bizarre history of literary relic hunters, the troubled legacy of Robert Lowell’s late-career sonnets, and the golden age of the American video game arcade. In 2023, Hilbert served as North American campaign manager for A. E. Stallings’ successful campaign for the appointment of Oxford Professor of Poetry. Hilbert was awarded the 2023 Meringoff Writing Award from the Association of Literary Scholars and Critics and accepted the award at the annual conference at the University of Houston. In the fall of 2023, Hilbert was poet in residence at West Chester University in Pennsylvania. His poems have been translated into Danish, Norwegian, Spanish, and Czech.

Hilbert writes opera libretti and lyrics for composers Stella Sung, Daniel Felsenfeld, and Christopher LaRosa. He has collaborated on scripts for films and live concerts staged by the post-punk conceptual band Mercury Radio Theater (he has also appeared live with them). Hilbert recorded a spoken-word album and performed live with the band Legendary Misbehavior. He performed his poems at an interlude during performances of Bach cantatas by The Trinity Choir and Baroque Orchestra conducted by Julian Wachner at St. Paul’s Chapel in New York City. Ernest Hilbert’s poem “Riddle Me,” written specifically for use as NFT (non-fungible token) art, was listed for sale using the cryptocurrency Bitcoin through OpenSea, a peer-to-peer marketplace for rare digital items and crypto collectibles housed at the Hunter College MFA program in New York City; it was purchased by a private collector. Hilbert has written that although the poem “cannot lay claim to being the first poem (or item described as a poem) issued on the crypto market as an NFT, it is the first to use meter, rhyme, and repetition, which are ancient techniques essential to many uses of the art form throughout history.” Hilbert currently keeps a heavily-encrypted dark web poetry site called Cocytus and a more public website to promote his own events and publications called E-Verse Radio. In the late 1980s and early 90s, Hilbert played bass and wrote songs for the thrash metal band Judgement. The band received a remastered deluxe reissue of their studio and live recordings in 2023 titled The Final Decree from Thrashback Records.

Hilbert graduated with a doctorate in English Language and Literature from Oxford University, where he edited the Oxford Quarterly. While there, he studied with Jon Stallworthy—biographer of Wilfred Owen and Louis MacNeice and editor of the Norton Anthology of Modern Poetry—and James Fenton, then Professor of Poetry at Oxford. Hilbert later served as poetry editor of Random House’s magazine Bold Type in New York City and editor of Contemporary Poetry Review, published by the American Poetry Fund in Washington DC. In 2003, he hosted an evening of readings at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City, entitled “The Future Knows Everything: New American Writing.” He has been interviewed on NPR and NPR-affiliate stations, as well as Sirius XM Radio, and the Poetry Foundation’s “Poetry Off the Shelf” podcast, and his poetry has been read on WPSU/ PBS’s Poetry Moment series.

For over a decade and a half, Hilbert hosted the E-Verse Equinox Reading Series, which he founded, at Fergie’s Pub in Philadelphia. Over that time, he shared duties with co-hosts Paul Siegel, John Wall Barger, Spencer Short, and Luke Stromberg. Featured readers during the series run included Chad Abushanab, Sarah Arvio, Laynie Browne, George David Clark, Eduardo C. Corral, Gregory Crosby, Thomas Devaney, Michael Dickman, Timothy Donnelly, Jehanne Dubrow, Daisy Fried, Warren C. Longmire, Jennifer McCreary, Paul Muldoon, Kathleen Ossip, Iain Haley Pollock, Catie Rosemurgy, Alexis Sears, Vijay Seshadri, Robyn Schiff, Afaa Weaver, David Yezzi, and Matthew Zapruder.

He works as an antiquarian book dealer in Philadelphia, where he lives with his wife, Keeper of the Mediterranean Section at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology and their son, Ian. Hilbert’s full career biography appears at the bottom of this page.

ON THE POETRY OF ERNEST HILBERT

Ernest Hilbert’s Storm Swimmer is a gleaming cornucopia of dreams, nightmares, tenderness, and grace. In Hilbert we encounter the poet as allegorical realist: a seer who has “known beauty almost impossible / To believe, nearly always lost amid / All the usual distractions.” This is a rare book, both willing and able to capture the wide and relentless range of the human condition in its varying lights and shadows, and in settings spanning the mundane, the tawdry, and the sublime. Storm Swimmer is a book of great feeling and of great technical skill. Everything in it is sacrificed for poetry, which is why everything in this beautiful book lives.

– Rowan Ricardo Phillips, author of Living Weapon

* * *

I’m deeply moved by Ernest Hilbert’s new collection—his fifth—called Storm Swimmer. That title captures the harrowing action of this book perfectly. In these poems, the joys of fatherhood are hounded by the certainty of death, the undeniable delicacy of human life set against the beautiful chaos of nature. But ultimately it’s not the shadow of despair that colors these pieces; it’s the flame of his resistance. “I know we’re dust,” he writes, “and stardust too, but more.”

– Ron Charles, Washington Post Book Club

* * *

Just as all life once sprang from the sea, so too do the subjects and strengths of these poems. The work of an experienced poet approaching the height of his powers, Storm Swimmer truly is a collection—to modify a phrase from Norman Maclean—both haunted and nurtured by waters.

– The Spectator

* * *

In Storm Swimmer, fatherhood is neither one-dimensional nor short-sighted; instead, fatherhood is a nexus, rigged with grace and curiosity—an enduring gift for a son and for readers. Toggling between the natural world and the relentless spectacle of contemporary life, acutely aware of the passage of time, Ernest Hilbert’s poems are marvelously built, resonant.

– Eduardo C. Corral, author of Guillotine: Poems

* * *

Lowell once again seems not only to hover over but energetically to inhabit these verses [Storm Swimmer] with their “hard linebacker waves” and thinly veiled Christ child who “has come to conquer death.” Lowell’s Atlantic breakers are accompanied by A. R. Ammons’ coastal journeys, milder but just as various with their human flotsam and jetsam. Richard Wilbur’s generation showed us what they learned from Auden, but to hear this note struck by Hilbert, one of his generation’s most interesting poets, is encouraging. He has a sense of generational inheritance.

– The Hudson Review

* * *

Ernest Hilbert’s Storm Swimmer is a book of light and darkness enacted on scales personal (particular and intimate in its rendering of the bonds of fatherhood) and sweeping (societal, environmental)—often simultaneously. Throughout, the ocean’s push and pull is literal—littoral—and figurative—metaphorical, yes, but also “representing forms that are recognizably derived from life”—all definitional italics mine, of course, though the emphasis is all Hilbert’s, a patterning of attentive sound, sight, and specificity that calls to mind Gerard Manley Hopkins’s instress, inscape. While the sublime of the natural world carries its own beauty and terror in Storm Swimmer, the booty and error of the Anthropocene, freighted with consumer stuff and consuming violence, pulls the reader in (and under) as well. As the book tips past its midpoint, we see ourselves in the storm (the repetition of “We’ve never seen a storm like this before” in “Visitation”); we see ourself in the oceanic depths (activated in “Range” by a gun’s report “Surging on the seafloor of my skull”). In Hilbert’s poems, the internal and external blur, while the language lights a way forward through the fog.

– Dora Malech, author of Flourish

* * *

Ernest Hilbert’s ambitious book Storm Swimmer—it includes epigraphs in Greek from Homer and Apollonius of Rhodes—is a meditation on fatherhood and on the human legacy bequeathed to a young son, culminating in a poem appropriately indebted to Coleridge’s “Frost at Midnight.” But this tender domesticity also achieves a pelagic reach, as the collection begins and ends with ocean swimming. The fact that one of its maritime settings is Corson’s Inlet on the New Jersey shore, where poet A. R. Ammons revolutionized the relation between thought and poetic line in a way that sparked Projectivism, is indicative too of the verbal and formal resourcefulness of this collection. And its cultural range is no less wide—from Mozart’s K. 265 or Fauré’s Requiem to a Heavy Metal tribute night.

– Karl Kirchwey, author of The Engrafted Word

* * *

Storm Swimmer is a rich, rewarding book. These are poems to get lost in.

– Luke Stromberg, author of The Elephant’s Mouth and Other Poems

* * *

Ernest Hilbert has always written from the ragged edge between tradition and the present moment, and now he goes for a deeper immersion, a swimmer in life, aware of its most desperate and beautiful currents. Here we have the consolations of family life, but also the desolation and waste of pornography and the art world—even rhymed couplets on a semi-automatic pistol. The sea has taught him to ride out the detritus of existence, to see it but not be consumed by it, and his forms give spine to his vision. Storm Swimmer is his strongest book so far, urgent and real.

– David Mason, author of Pacific Light

* * *

Hilbert, one of our greatest contemporary poets, writes of psycho-mythical rapture as easily as garbage and urban decay, oftentimes in the same poem. A master of the seedy vignette, the deliciously vivid image, the imaginative flight of fancy, Hilbert has recently explored poignant new dimensions of paternal love and mortality, proving ever more definitively that there is nothing he cannot do.

– Loganberry Books

* * *

Tough-minded and precise, Ernest Hilbert’s lyrics, like his old mirror left out at the curb, turn an unflinching gaze on pieces of inner and outer landscapes we often push to the periphery. The poems in Caligulan fashion a stern, witty, and often poignant music out of seemingly unpromising elements courageously glimpsed, combined, or imagined.

– Rachel Hadas, author of Halfway Down the Hall: New and Selected Poems and editor of The Greek Poets: Homer to the Present

* * *

Hilbert unerringly assumes the burdens of clarity. He knows the thing and has no lack of means to tell you about it, ravishingly. He pummels the sonnet-form back to life, breathing into it the whiskey-breath of the here-and-now. Hilbert has a gift for simile, metaphor, and phrasing. I can picture Hilbert in a drunken brawl with Christopher Marlowe. I mean this as a compliment. Hilbert holds his own.

– The New Criterion

* * *

Both in title and subject matter of the many of the poems, Ernest Hilbert’s Storm Swimmer, winner of the 2022 Vassar Miller Prize in Poetry, engages with natural forces in a way relatively unique in the modern world, one in which he is truly encompassed by them. Poems like “Storm Swimmer” come alive in moments of true immersion in waters alive in seldom perceived ways.

– North of Oxford

* * *

These sixty new sonnets [All of You on the Good Earth] find Ernest Hilbert, “an earnest / Pilgrim of some kind,” charging up to the ruins of a shared and personal past as well into the ether of his own (mostly) earthbound head. Part shaman, part showman, he reaches his hand in, winks, and with a flourish, produces one little marvel after another. Like Lowell before him, Hilbert has found in the sonnet a form of confinement that excites and accommodates a liberality of temperaments, rhetorics, bad thoughts and big ideas, but where Lowell favored blank verse, Hilbert surprises with rhymes he unwinds with preternatural finesse. His material ranges from the all too familiar to visionary moments in which our debauchery brings us to “fall apart like ancient stars” or to witness a vaseful of stargazer lilies “unfastening like a vast nebula” with a “long pour of poisonous gas.” Retrospective, forward-looking, tonic and toxic, All of You on the Good Earth is a wonder of a book, and Hilbert’s best yet.

– Timothy Donnelly, author of The Cloud Corporation, winner of the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award

Ernest Hilbert’s sure-footed poems have the breathless urgency of a man telling others the way out of a burning building. Unafraid to startle, often winning out over recalcitrant material, they score astonishing successes. A bold explorer with few rivals, Hilbert enlarges the territory of traditional form. Sixty Sonnets may be the most arresting sequence we have had since John Berryman checked out of America.

– X. J. Kennedy, author of Lords of Misrule and editor of Literature: An Introduction to Fiction, Poetry, and Drama

* * *

Ernest Hilbert has an enviable ability to speak about contemporary America as if his words were washed in the blood of Achaean soldiers. Hilbert, speaking to the violence underlying human nature, sees war everywhere. Watching the Super Bowl in his living room, the football players—”Towering champions, created to win, // Will strut to their positions and pose, / Burnished, armored in emblems”—become iron age warriors. Outside his house, birds swerve “in squadrons.” “The border of the republic,” says the speaker of “Mars Ultor,” “Is breached without notice: / More tug of war / Than elegant chess.” This refers to Romans preparing for battle—but also to Donald Trump. In fact, “Mars Ultor” was read aloud at the Trump Tower by (highly literate) protesters. In Last One Out, Hilbert—as with many poets writing at the heights of their powers—conveys a sense that we are being told a single narrative of human existence, that each poem is a small part of a larger mosaic, being revealed to us slowly.

– Literary Matters, Association of Literary Scholars, Critics, and Writers

* * *

Hilbert has an appetite for life equal to his taste in literature: a rare combination in an age of dissociated sensibility. In these sonnets, whose dark harmonies and omnivorous intellect remind the reader of Robert Lowell’s, Hilbert is alternately fugitive and connoisseur, hard drinker and high thinker. But he is always a true poet, proud to belong to the company of those who still feel “The last, noble pull of old ways restored, / Valued and unwanted, admired and ignored.”

– Adam Kirsch, author of The Modern Element: Essays on Contemporary Poetry and The Global Novel: Writing the World in the 21st Century

* * *

The comparisons to Lowell are just . . . What’s so attractive here is the colloquial nonchalance that transpires within the formal decorum. It’s quirkier, more low to the ground, more hip, as one said in the olden days. “You should know I’ve come to terms with weather / since you left.” This made me laugh out loud.

– James Longenbach, author of Modern Poetry after Modernism

* * *

Ernest Hilbert is a formalist, and a skilled one. He is well aware of the poem’s ability to wrest itself away from the poet (this is, after all the subject of “Kite”), but he is also aware of the shaping power of the imagination, and how it can redeem a world of dread. It is this exalted sense of the power of the act of poetic making that truly marks Hilbert as a Romantic, more so even than his love of nature or his occasional flirtations with the notion of the alienated poète maudit. And, while the poems of Caligulan come to us from a political era now ended, this faith in imagination as a cure for pervasive dread marks Hilbert as an important poet for the new and dreadful era of American public life upon which we are now entering. It will be a Caligulan time, for which we will need books like this.

– Literary Matters, Association of Literary Scholars, Critics, and Writers

* * *

Ernest Hilbert’s Last One Out is full of a tender masculinity, fatherhood, unfathering.

– Poetry Foundation, Reading List, May 2020

* * *

When one opens a book of poems and sees the music of words become a spell for opening up of experience, for bringing back childhood, for seeing ourselves inside these “long days that fill with night,” one knows one is reading a true poet. Ernest Hilbert’s poems don’t shy away from the world. There are public poems here, and very private songs, there are also poems that are unafraid to look into the mirror and see “slow, confused motions of a ghost,” and poems that light our path through the darkness as if we are boys who hunt for fireflies and these poems in our hands “swim like wind-stirred lanterns.” There are lines which make me think of Seamus Heaney’s way of mining of human experience not to hear stories, but echoes. To hear the music of those echoes between our days is no small thing. It takes a true artist, it takes someone who can make a poem of just a few lines wherein time pauses, and silences come out—and become visible, while “the light is leaving and windows brighten / across the street.” Last One Out is a very beautiful book. It sings.

– Ilya Kaminsky, author of Deaf Republic and Dancing in Odessa

There are plenty of people who have declared themselves poets, but not nearly as many poems worth reading. Ernest Hilbert’s, however, take their readers seriously. Mundane stuff, like tubes of sunscreen, are described in new and bracing ways (“Kinked at center, cargo of clouds squeezed out”), and even at their grimmest, his lines are alive with wit (“We boil horses and harness girls to tow / Corpses”). These are well-made, moving poems, designed with our pleasure in mind.

– Jason Guriel, author of The Pigheaded Soul: Essays and Reviews on Poetry and Culture

* * *

Non omnis moriar, “I shall not die completely,” Ernest Hilbert attaches this motto to his latest book of poems, and it makes sense. Last One Out is a book haunted by loss: besieged and ruined cities, a blasted tank abandoned in the desert, incinerated houses sifted for what trinkets of past lives remain. It begins with the poet’s grandfather and father—both long dead—and continues with an atavistic yearning to enter the past and drag it forward into the present. The book isn’t a lament, though: it’s a journey, taking us from images of the poet as bereaved son to a portrait of the poet as protective and loving father. Take the trip.

– Robert Archambeau, author of Inventions of a Barbarous Age: Poetry from Conceptualism to Rhyme

* * *

The work of art that moves through summer to spring is the work of an optimist. So don’t let the title fool you. As the star under which the poems in this collection move, the title Caligulan is brutal and yet beautiful, highly refined and yet enticingly diurnal. Moved by beauty, attuned to the sublimity of natural things, livened by paradox, coaxed into song by pentameter, Ernest Hilbert’s rich new book covers more emotional ground than a reader has any right to expect of a poet writing in this muted and mumbling world we have made for ourselves. “Caligulan” poems like “Squirrel Hill” are hard to come by. And when you come to them you feel grateful for such a luscious reminder of how poetry can honor the life lived, the lives taken from us, and the life still to be lived. Indeed, Caligulan is a timely reminder that the only tyrant that can take poetry away from us is us.

– Rowan Ricardo Phillips, author of Heaven and Blackness Rhymes with Blackness

* * *

Ernest Hilbert has written some of the most elegant poems in American literature since the loss of Anthony Hecht. A fascinating blend of the Augustan and Romantic (an Augustanism that flirts with the sweaty Rochester as much as the marmoreal Johnson, and a Romanticism charged with as much street grit as lyricism and longing), with a cadence that can be as wickedly eloquent as Lowell or compressed, as an elegantly held fist, as Bishop, Hilbert holds tight to an understanding of poetry and the role of the poet—proud without complacency, authentic without cheapness, self-respecting and self-mocking—that is (thank God) not particularly popular in poetic circles today . . . He, or his poetic persona, moves across the world, an “earnest pilgrim,” from the necropolis at Vulci to Iwo Jima, to the bars of TriBeCa and the back alleys of Queens, to Senecan Rome, “from Grub Street to the Brill Building,” to the “dark suburbs” (“The insatiable sprawl thieves as it gives,” as he says in a memorable line in a book packed, jammed, and o’erbrimming with lines you will want to linger over, savor, like the wines of Helicon), to New Jersey’s Mullica River, to a graveyard in Philadelphia . . . Any page you open to contains, not a gem, but a treasury, a manuscript of illuminations, lapis lazuli and gold, even when the poet is watching his key chain spatter down a toilet bowl in a late New York club night. He describes, like a Milton cast away in the alleys, what he sees on a bleak night in the slums of a great, wounded city, or in the hungover misery of a bus ride down the east coast’s suburban sprawled flank, in a poverty-stricken childhood home life among “the peculiar clan at cul-de-sac’s end,” in the fissile fossilizing of a convention of archaeologists, in a list (far from incomplete) of America’s robust negatives, in a pixilated Oscar acceptance speech and a rancid envy’s tongue lashing of revenge—all without missing a beat or a foot.

– Christopher Bernard, Synchronized Chaos

* * *

When a formal poem is doing its job well, it couldn’t exist in any other way. In All of You on the Good Earth, Ernest Hilbert takes on the sonnet form with every poem. At their best, Hilbert’s poems use that form to full advantage, revealing depths of meaning that would otherwise remain inaccessible . . . . If you’re interested in formal poetry—or even if you’re not—do yourself a favor and check out Hilbert. With work appearing everywhere from American Poetry Review to Yale Review to B O D Y to Rattle, he’s poised to become a major voice in contemporary formalism.

– Cleaver Magazine

* * *

Hilbert has a tough, unsentimental vision of contemporary life. One review of his new book, Caligulan, calls it “an honest volume for dishonest times,” partly because the poems don’t rest any more easily in traditional poetic forms than they do in free verse, and partly because his scenes are often so full of unease, dis-ease, death, and things gone awry. Steeped in tradition, the poems are also street-smart and utterly unacademic. His first full-length book, Sixty Sonnets, inaugurated a form now called “the Hilbertian sonnet”—a very workable variation on Petrarch and Shakespeare. Hilbert is one of the very few poets ever to have a verse form named for him, which is surely some kind of honor. As it happens, I read a lot of contemporary sonnets, and most of them bore me to tears. The best in the Hilbertian mode have a jangly, new-fangled music that never settles into formalist quilting bees. His second full-length collection, All of You on the Good Earth, continued in that vein, extending the range of subjects if not the form. Caligulan not only brings a new and disturbing adjective into existence

, but also proves Hilbert a poet of greater intellectual and formal breadth than we might previously have realized. Hilbert is a poet of psychological restlessness, of urban and sometimes rural scenes in which cruelty is natural and grace sometimes hard to find. But the hard-earned grace of his work will linger in the mind and the heart.

– David Mason, editor of Twentieth Century American Poetry and Western Wind: An Introduction to Poetry

* * *

The poems of All of You on the Good Earth are tighter and brighter than those of Sixty Sonnets. It’s clear that Hilbert’s verse is not “sentenced to stay still.” The book “rolls and glows” through another sixty sonnets (an appellation one should not utter in Mr. Hilbert’s presence unless you’re buying a copy of the book from him and a drink for him) with an ear that has developed beyond what A. E. Stallings called “the roughed-up prose rhythms of speech” in Hilbert’s first collection. Far more than his previous work or the work of most other poets today, Hilbert in All of You on the Good Earth lets his poems live within the sound of words, meaning not subordinated to sound like in a Stein poem but enhanced and enlivened by it as in the best words of Eliot or Plath. This is a fine collection.

– Literary Magnet

* * *

Hilbert’s stance is that of the outsider, the rake, the poète maudit; he is drawn to the monstrous, the grotesque, the wounded, solitary, and absurd. Like his masters, Lowell and Berryman, he writes with one eye on the canon and the other on the bottle . . . among the voices channeled here are a fiery street artist, a vatic gravedigger, a Roman stoic, a judgmental suburban village chorus, a pompous aesthete, a depressed, aging singer, a spaced-out actress at the Academy Awards, Newbolt man (homo Newboltiensis) on the fields of Eton, a beleaguered war correspondent, and Benito Mussolini, pleading for his life. The poems take place at sea and ashore, in boats, parks, cities, and ancient ruins, on trains and in cars, at loud strip clubs, seedy apartments, and reputable estates, in zoos and at archaeological conventions. They are lyrical, moving, angry, sad, wistful, and funny.

– Hopkins Review

* * *

In his debut collection, Sixty Sonnets, Hilbert establishes a variation on the sonnet form, employing an intricate rhyme scheme and varied line length. A skillful practitioner of form and nuance, Hilbert shifts between delicately sonic moments and humorous narrative sequences. Hilbert’s second collection, All of You on the Good Earth, returns to his idiosyncratic, highly inventive sonnet form.

– The Poetry Foundation

* * *

Ernest Hilbert has dared to wear the mantle of the public poet. Critics often compare Hilbert to Robert Lowell, not only because he allows his personal demons a say in his poetry, but also because, in many of his poems, his intended audience is not one reader or a small group of aficionados, but our nation, these hardly-united States—whether or not our nation is willing to listen.

– Newburyport Literary Festival 2020, “Public Poems and Private Songs: The Poetry of Ernest Hilbert”

* * *

The point is all-inclusiveness, acceptance of the whole world of subject matter. [All of You on the Good Earth] means to take in the beautiful and the awful, and it does; its publicity tells us that it “continues to explore the bizarre worlds of twenty-first-century America.” The attractive cover design, purely color and text, avoids any interpretive tilt, neither approving nor condemning that bizarreness. The index of the book’s cultural references runs from Alighieri to Zevon, through Nick Cave and Montaigne and Wilde and assorted others on the way. To get everything here, the reader needs to be able to parse a little Latin and a little Italian and have a purchase on most of Western history, poetry, movies, and television. The breadth is consonant with the list of accomplishments in the poet’s bio. The small, witty touches that enlivened Hilbert’s first book are here too—for example, the sly statement on the copyright page that resemblances to actual persons are “of course, purely intentional.” Close observation in all things, low or luxuriant, is the great strength of the poems . . . The best we can do with the sad strangeness is to look carefully and take the marvels where we find them, admitting that they never finally wipe away the tears of things. . . . It’s a poetic stance we can believe in the twenty-first century. It’s a significant one, in a poetic world that has become, in David Yezzi’s phrase, “like a spayed housecat lolling in a warm patch of sun.” Hilbert’s is a voice we can trust and be grateful for as a way of making sense of this bizarre, and sad, and laughable—and good—Earth.

– Angle, Journal of Poetry in English

* * *

After his beautifully rendered Sixty Sonnets and the eloquent All of You on the Good Earth comes this richly wrought new collection. Hilbert is a classicist in the finest sense of the term: he has a firm grip on the formal orders that have dominated the great tradition of Anglophone verse from the skalds of Beowulf and the Pearl Poet to the tight gems of darkness of Thomas Hardy, and he uses them to write poems that ring with very contemporary truths. A skillful artificer of forms of verse that have sometimes gone wanting or are unjustifiably neglected or despised after the earthquakes of modernism, he is afraid of neither tight meter nor demanding rhymes: he proves there is nothing whatsoever anachronistic about well-tooled verse; the rage of authenticity can speak as sharply in a sonnet as in a calligramme . . . Though a constant trembling of anguish informs many of these poems, like a quiet ostinato rumbling constantly in the bass, what is most notable is how the poet’s anxieties are, in the main, transmuted from personal spasms of what sometimes feels like merely neurotic terror into objects of great beauty, a beauty that transforms the anguish that generated them into victories, however temporary, of grace.

– Christopher Bernard

* * *

Caligulan delivers on all of its title’s promise. Every poem evokes the world we live in: we know something is wrong and, in a minute, will likely be worse; but there’s beauty in the portent and in the self-awareness we need to see it. Hilbert’s remarkable ability to draw a scene so clear you immediately make yourself at home, and so suggestive you want to get out because you know you can’t settle in, makes this collection a page-turner in a way most poetry books can never be.

– Erica Dawson, author of When Rap Spoke Straight to God

* * *

Just as the work of the modernists showed that the best free verse usually has something masterfully formal about it, Hilbert’s fine collection [Sixty Sonnets] might serve to remind us that the best formal poetry has about it a marvelous colloquial freshness and inventiveness, and the ring of an actual human voice. It is a touching and intelligent book.

– Franz Wright, recipient of the Pulitzer Prize for poetry

* * *

Sixty Sonnets delights in a decidedly badass bravura. Hilbert’s red-blooded diction and febrile subjects put paid to any lingering suspicions about traditional verse’s chronic anemia. His erudition is salted with humor, his romantic flights with a rage for order. He is a twenty-first century beatnik in Elizabethan ruff. A smashing debut!

– David Yezzi, author of Azores and The Hidden Model

* * *

There’s much pleasure, clarity, and discipline to the way Ernest Hilbert looks around him in Caligulan, at the complicated textures of city and landscape, and at all the stuff, the materials, the detritus, that make up a place, a time, and a life. In these easily formal, easily idiomatic poems you’ll read about a dishwasher—his “arsenal of cutlery, / The spider-eggy fluff / That clings like mold to crockery”—and you’ll also meet the stuffed moose at a science museum: “You still startle, filling half the false sky . . . . // You tower / In the same black forests I’ve traveled lately.” Hilbert gets the details right, and he also gets the emotions right. “The smoke alarm fails, and your computer crashes” while an ATM is “pitiless, displays a message for / Insufficient Funds.” But there’s also this: “You want to fight. / You spit and shout. In daydreams you sing.” This is a book full of the real, and also full of heart.

– Daisy Fried, author of Women’s Poetry: Poems and Advice

* * *

Ernest Hilbert’s Vassar Miller Prize-winning Storm Swimmer explores the quieter rewards of fatherhood and memory—the sort of humane vision that online life threatens to eclipse. In this, Hilbert’s fifth book, storms (including interior ones) swirl and rage, potent in action or as lurking threat. Ernest Hilbert’s Storm Swimmer, so remarkable for its style and polish, is most impressive for its kindly, meditative depths.

– Literary Matters

* * *

The American lyric rendered in these poems follows Coleridge’s description of the sonnet as “adapted to the state of a man violently agitated by a real passion.” Hilbert’s passion here is to contain, precious piece by precious piece, the unordinary quotidian of the American poetic. Sixty Sonnets is a gift to all of us from an exceptional ear and a fine consciousness.

– Afaa Michael Weaver, author of Multitudes, editor of These Hands I Know: African-American Writers on Family, recipient of the Kingsley Tufts award

* * *

For scale alone, the project at first seems improbable. But then you read, and it’s clear that Hilbert’s sensibility, bright-hued and gothic, sentimental, precise and ambitious, could be contained by no less. These wry and lovely poems are for anyone whose curiosity ranges from Petrarch to improv, and the result is a complex portrait of the America of our current era—composed in singing verse!

– Dave King, Rome-prize winning author of the novel The Ha-Ha

* * *

A fine book [Caligulan], circling environments ancient and modern, while evoking a subtle malaise of spirit in our current moment. A line from the title poem, “lightning blackens your temple,” startles in its perfect combustion of image and emotion, a quality found in every poem.

– Ryan Blacketter, author of the novel Down in the River

* * *

The poems in Caligulan have a wonderful resonance. These new poems have something very “Cal” [Robert Lowell] about them, the very personal tone and settings combined with extraordinary perceptions. The fishing boats in “Barnegat Light” returning “as silhouettes” is a haunting, beautiful image. At unexpected moments, Hilbert reaches for, and finds, the sublime.

– Michael Steffen, introduction at the Hastings Room Series, Cambridge, Massachusetts

* * *

Reading Ernest Hilbert’s poetry, the first thing you notice is the absolute mastery of form and acoustics, the like and force of which are nearly unparalleled in American

letters.

– Hugh Sheehy, author of Design Flaw: Stories

* * *

Hilbert’s poems are filled with images of other worlds, lost worlds, ancient Rome, a series of Atlantises, the detritus of wars long covered over in dust and rust. These places, things, contain messages—incomprehensible, garbled, or lost—to this very observant man. Hilbert is haunted by what used to be here, either 20 years ago or 1,500 years ago. Sometimes the past sits on top of the present, kind of like those digitized holographic images which show you what a landscape looks like pre- and post-hurricane, or how a New York block changed over time. Hilbert never just sees “Now.” Hilbert’s honesty is not just refreshing, but revelatory.

– The Sheila Variations

* * *

Like the minutes of the hour, these Sixty Sonnets both combine to make a whole and shine as individual moments. While groups of these sonnets occasionally suggest a narrative—refreshingly, like the fugitives and weary academics that people these pages—they work alone. The newspaper crime blotter itself, from which, perhaps, some of these incidents are torn, speaks up as a single sonnet. Here are barflies, high-school dropouts, retired literary critics, washed-up novelists and war-zone reporters, suburbanites and historians, and lyrics with a range of reference from Zippos and Star Wars figures to George Gissing and Thomas Eakins. Mostly in a decasyllabic line that allows for the roughed-up prose rhythms of speech, these sonnets tend to conclude in true iambic pentameter, the tradition that haunts rather than dominates these poems. It is the voice of a less lyrical Prufrock (“We’ll head out, you and me, have a pint”), a voice that speaks with unsentimental affection for the failures, the “fuck-ups,” the “Gentlemen at the Tavern”—but it is a voice that just as easily could be speaking of the gentlemen at the Mermaid Tavern, and indeed there is something of Marlowe, as well as Eliot, in this sensibility. The evasive presence in the background occasionally speaks in propria persona—the wry, worldly-wise voice of the poet himself—as much listener as talker—something like a sympathetic bartender, scrupulous in his measures, who has heard it all before, but nightly observes every hour unfold afresh from behind the counter.

– A. E. Stallings, MacArthur Fellow, poet and translator of Lucretius’s Nature of Things for Penguin Classics

Hilbert is one of our best rhymers since Robert Frost, and his poems have been compared by superb poets to those of John Berryman and Robert Lowell. We haven’t had a poetry like his—both seriously tough-minded and wryly self-chiding—to enjoy and mull over for a long time.

– Alice Quinn, Executive Director of the Poetry Society of America

* * *

Ernest Hilbert [possesses] a wealth of imagination wedded to honesty of insight, integrity of vision, respect for form, and delight in the harmonies of language (including a strong appreciation for the Anglo-Saxon roots of English prosody that subtly inflects his own practices) that is second to none. His latest book, Last One Out, his fourth major collection, establishes him, I believe, as one of our leading poets. I always expect rich, fine gifts from Hilbert, and always get more than I expected. Last One Out is elegant and athletic, eloquent and brave, deeply thought and felt; the work of someone who, if we survive, may well become one of our classics. Poems like these helped make me fall in love with poetry when I was a teenager. May they have the same effect on some young reader today.

– Synchronized Chaos

* * *

As anti-pastoral as Hilbert can be, he shares Robert Frost’s commitment to describing impressions as precisely as possible, which may offer, as it did Robert Frost, a “momentary stay against confusion,” even if such descriptions can lead to contradictory conclusions . . . . The music of Caligulan is, by turns, smooth and jagged. This is by design. Poetry reflects and clarifies complexity . . . . An honest volume for dishonest times, Caligulan reminds us that “thunder / Sinks your song, because, like the day of birth, / The day you’ll wake and have your death is set.” It “just hasn’t happened yet.”

– Washington Free Beacon

* * *

Ernest Hilbert’s Sixty Sonnets is exactly what its title suggests—and thus it’s a performance as much as a book of poems, showy and spectacular. From the brisk noir of “She Remembers How They Fled from the Liquor Store Robbery in New Mexico” to the ironic call-and-response of “Fortunate Ones” to the elegiac fatalism of “White Noise” Hilbert takes the reader on a bravura run through seemingly every variation of tone and style that the sonnet can contain. It’s a craftsman’s book, a revival of form best summed up by the opening lines of “Song”: “A song for those who learn forgotten, slow / Skills, crafts submerged long past by massed commerce.”

– Levi Stahl, poetry editor, Quarterly Conversation

* * *

* * *

Hilbert’s references are classical and contemporary. The world is beautiful and junky; our lives are marked by completely unexpected moments of happiness and regular bouts of boredom, depression, and self-destruction . . . . One of the things I appreciate about Hilbert is the understated realism of his work. He tries to capture—without theatrics or moralizing—what it feels like to live in the contemporary world. In fact, realism is a kind of ethic for him. His work is, in many ways, about facing the suffering and cruelty of life with honesty and courage.

– Prufrock

* * *

[Sixty Sonnets] delivers the full range of human types and stories, and nearly the whole breadth of what the sonnet can do. . . . We might see Hilbert as being God in these poems—as taking the all-gathering view of the merciful God who has room for all these lost ones, right along with the desperate fugitives, retired literary critics, crime victims, lovers, and godfathers. The poet as indwelling creator spirit? It fits for Hilbert: poet, from poietes, maker.

– RATTLE

* * *

Ernest Hilbert’s poems are beautifully made in their diction. The intelligence is clear.

– Donald Hall

* * *

The only other poet who plies risk against reward so deftly is Pound.

– Strong Verse

* * *

I took great pleasure in All of You on the Good Earth. [Hilbert has] a fantastic command of form that is bolstered by vernacular. I love the ending of “Soprano’s Lament,” for example. There’s a wonderful diction that reminds me of my favorite poet, Auden, and also a dash of Ted Berrigan of the sonnets. [Hilbert’s] touch is always of the best mind but also the down-to-earth perspective–radios paint-speckled, sirens, pissing lynxes.

– John Skoyles, author of Secret Frequencies: A New York Education

* * *

Without abandoning his previous technical achievements or his stark vision, the poems in Last One Out move in a new direction. Primarily, the shift is in the voice of the poems. The anarchic sneer and the guttural growl of the earlier books have mellowed somewhat into a more meditative and resonant speech, a voice so commodious even wisdom statements may find room within it . . . Ultimately, Last One Out is a kind of satura: consisting of 53 poems in seven sections, it is various in its forms, its subjects, its tones, and its genres. There are ekphrastic poems, love poems, historical poems, satires, memory poems, occasional poems, elegies, narrative poems, and mythical poems. What binds this bravura together is Mr. Hilbert’s penetrating vision and expansive voice, still adept at scorn but now capable also of a kind of heroic delicacy.

– The Hopkins Review

* * *

[Hilbert’s] that rare thing these days, a sonneteer, but he brings a conversational vibrancy to the form that continually pushes against its constraints even as it draws strength from them. And, oh, the pleasures he takes in sound and rhythm and rhyme! “Taped up, damp now, smeared photo of the stray / On each scratched steel lamppost along the way.”

– ivebeenreadinglately.com Book of the Year (Poetry), 2013

* * *

Ernest Hilbert’s latest book, Last One Out, lacks some of the public or Horacian spirit and humor of his early books of sonnets, but compensates by giving us poems vivid of line and image and more somber in their depth. Early in the book, several poems recall his late father, who was a church organist. Hilbert’s poems often sound like the work of a classicist with a taste for heavy metal, a bit like Oxford and south Jersey mixed knowingly together—as if he were trying to figure out how one can still live a civilized existence in an age of detritus and decay.

– First Things, Our Year in Books: 2020

* * *

Ernest Hilbert is known for the sonnet, and rightfully so. In Caligulan, he doesn’t so much break free of that form but makes it clear that whatever he does, whether with subject, verse form, or anything else, it’s because it’s what he damn well wants to do. Caligulan is both the most formally varied and the most thematically profound of his books. The dark wit of his first book, Sixty Sonnets, has deepened into a more mature darkness that, like the title Caligulan itself, owes something to Robert Lowell but is in no way derivative. This collection finds an important American poet coming into the height of his powers. These poems will make you laugh and break your heart even as they drink you under the table.

– Quincy Lehr, author of Dark Lord of the Tiki Bar

* * *

“[Storm Swimmer provides the] gift of the opportunity to revel in the music of the flow of his ideas. [Hilbert is] a true maker.”

– Marc Simon, editor of The Complete Poems of Hart Crane

* * *

A perfect book for our times.

– Robert Archambeau, author of Poetry and Uselessness: From Coleridge to Ashbery, on Caligulan

* * *

Caligulan may have a lurid cover and title and you may be able to purchase t-shirts advertising the book in a bespoke heavy metal font, but such paraphernalia should not distract us from Hilbert’s very high ambitions for his poetry. Individual poems can function in a similar manner to the book as a whole: distracted by his sometimes disheveled persona, you may want initially to compare this poet to someone like Bukowski, which is by no means a mean comparison to make, but I think that Hilbert writes very carefully to make himself heir to Shakespeare, Milton, Wordsworth, and Wallace Stevens.

– Edward Clarke, author of The Vagabond Spirit of Poetry

* * *

Hilbert insists that perspective, where and how we are when we observe, is everything. . . . Just as Hilbert observes his modern world, he also reflects on the past, not his past, but that of humanity. He does so as if he were there, as if he were able to time-travel and seize these moments for future examination. A denizen of the present and an admirer of the past, Hilbert doesn’t overlook the not-so-pristine images of industrialism or modernity, but he also does not herald the great histories. Instead, he delves into both, mixing old and new, reaching for truth as he sees it, using one of the most classical literary forms, each sonnet a small window looking out to the larger view.

– Glassworks

* * *

Who gets away with rhyming “looker” and “fuck her”? Ernest Hilbert does, that’s who. And who among us has a sonnet form named after them? Why, it’s Ernest Hilbert yet again. “Be glad you’re not too stupid, or too short,” he advises, being neither of those things himself.

– Jill Alexander Essbaum, author of Heaven, Harlot, and Hausfrau

* * *

Ernest Hilbert, in Sixty Sonnets, reminds us how vigorous and fun a form the sonnet is. That the form is still fecund becomes abundantly clear when one sits down with this collection and reads four, seven, nine sonnets at a sitting . . . These sixty leave one hungry for sixty more.

– Library Thing

* * *

Books of the year are those you know you’ll never bin; Sixty Sonnets belongs in their company.

– ivebeenreadinglately.com selection for Book of the Year (Poetry), 2009

* * *

Ernest Hilbert’s second collection of poetry, All of You on the Good Earth, is an enlightening example of the revival of the sonnet. The poems are intelligent, topically indulgent, and extremely well crafted. The sonnets are capsules, compressing large ideas or expanding small ones, lined up in equal measure.

– New Pages

* * *

Hilbert is at once ironic, dark, and witty. His lines reflect our own precarious hold on the world, where we are always close to losing control. From the perspective of an intriguing mishmash of subjects, Hilbert often takes on the persona of the failed, the beat up, and the beaten down, in which all are “sinking on a soft black balloon.” Hilbert entreats his hapless heroes to “go on, get high,” though there is always a price to be paid.

– Bookslut

* * *

Hilbert is masterful at rhyme. This is not over-the-top praise; his technique is simply awe-inspiring. Reading . . . the poems in this collection, a reader will mostly be unaware of his tremendous craft and only after search and analysis will his strict formalism become apparent. Nothing he does is obvious, his rhythmic constraints are unfelt, all of his seams are hand-sewn yet flawless and undetectable.

– Philadelphia Review of Books

* * *

Ernest Hilbert is one of the finest poets writing in the formal traditions of U.S. and European poetry. He is a master of craft, measure and music. His poem “Domestic Situation” has taken on the status of cult classic, widely performed and anthologized.

– New Dublin Press

* * *

All of You on the Good Earth is filled with gritty, vibrant, technically innovative and masterful poems that speak directly to how we live now. They’re dark, they’re funny, they can be quite tender, and they always observe the world closely.

– Conundrum Best Books of the Year 2013

* * *

Ernest Hilbert is a fierce intellect, who can dive into the pit and send back to the surface nimble prose and formal verse. He’s a poet who wields a two-edged sword, giving us sharpened 21st-century poems of life that are attentive also to the trailing edge of language, where old words and older ideas linger just as sharp.

– Henry Wessells, author of A Conversation Larger Than the Universe: Readings in Science Fiction and the Fantastic

* * *

Last One Out is pitch perfect, both in tone and musicality. One is stopped often by the sonority, the stunning lines and phrases embedded in the seemingly straightforward approach of the language. The insight, the intersection with the world, rings true poem after poem after poem. What a good book.

– David Sanders, author of Compass & Clock

* * *

Hilbert arrives before us by devious routes. Having received a doctorate from Oxford, we would expect him to show up in a faculty lounge, sporting tweeds—but the next chapter of his life begins in New York, on the punk rock scene. But just as we get used to the idea of Hilbert as raffish outsider, he shows up working for Random House and curating readings at the Whitney. Aha! We say. A Manhattanite creature of publishing and art! But just as we think we have him pegged again, he’s off to Philadelphia, to take up a position with America’s foremost dealer in rare books. And all the while he’s writing, writing, writing . . .

– 2017 Poets’ Prize Citation

* * *

The reader must be prepared to leap from ancient Greece to the East Village in one or two lines, and familiar with the Oresteia as well as Metallica . . . his is a quicksilver mind, generous and open and humorous.

– The Sheila Variations

* * *

Ernest Hilbert is not an optimist. In his latest collection, Last One Out, the title poem addresses not only our individual mortality, but a kind of “last call,” a “hurry up please it’s time” for the world as we know it. Nor is he a pessimist; the pessimist, expecting the worst, puts himself in the position of being sometimes pleasantly surprised. Rather, I think, Hilbert is a pejorist—things are going to get worse rather than better. It is a clear-eyed stance that nonetheless allows for some wonder at things as they are, some wry humor, some bonhomie. One day it will all be over, but even on that day, there will be hosting and toasting as well as ghosting. Last One Out is imbued with this feeling of belatedness, and serves both as a kind of middle of the journey reckoning and overview of career and ambition, but also a new starting out. The book’s epigraph is a tag out of Horace: Non Omnis Moriar—”I shall not die altogether”; something will remain. Is there possibly a glimmer of hope in this? With the title, Last One Out, perhaps it sets up an unresolved dissonance . . . “Masculine” in poetry might mean a rising rhyme suitable to Anglo Saxon monosyllables. The adjective recently most likely to modify it might be “toxic.” But Last One Out is an exploration of another species of masculinity—one of tenderness and gravitas, regret and responsibility, anchored by marriage and mortgage. Dedicated to Hilbert’s father, the book begins with a memory of his grandfather (“German/ With shoulders of granite, / Of beer and blue skies/ blast furnaces”) throwing him as a small child into a river to teach him to swim, and ends on a sort of agnostic prayer for Hilbert’s own young son, Ian.

– B O D Y Magazine

* * *

Hilbert excels with a somber palette—especially when he’s painting lines of the seafaring sort. “Ashore,” depicts a “harpooned great white shark” who’s washed up on the beach—dead. A crowd gathers to inspect the body. Hilbert is quick to remind the reader that, beneath the waves, lies “slit sails, drowned crews, [and] split hulls.” Setting aside visions of oceanic romance, Hilbert exposes the sea’s subtle haunting humanity. It’s a visceral must-read sonnet. But let’s not get too serious. Ernest Hilbert can have fun. Of all Hilbert’s poems in All of You on the Good Earth, there’s nothing like “Sunrise with Sea Monsters.” As a love letter to Ray Harryhausen (American producer and visual effects pioneer who created films like It Came from Beneath the Sea, 1955), the poem is a huge success, but it’s also something more. “The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms skulks / Ashore, hearing a foghorn, lonely for friends” writes Hilbert who also mentions the “clumsy frogman from the Black Lagoon” and “Nessie.” These are set pieces that, despite their hilarity, make us feel for these ugly mugs. They’re “[b]eaten back by ray guns, germs, and Marines” as sea gulls peer into the ocean “watching for the next poor monster.” We almost revel in their destruction. This rare moment shows that Hilbert can be humorous, albeit the dark sort. Hilbert supplies us with poems like “Nights of 1998” to keep things fresh. There’s an intense party happening downtown (drugs, drinks, fights, and puke included) in the speaker’s apartment and he’s attempting to make sense of the unfolding mayhem. “I’m lit like a war,” he says. What a fantastic line. “We fall apart like ancient stars, sparks— / Gold like pollen blown across all this dark” writes Hilbert. Suddenly, I’m back in space, watching the Earth, Ernest Hilbert’s Earth, rotate wonderfully, horrifically on.

– Apiary Magazine

* * *

The voice most characteristic of Mr. Hilbert’s work sounds something like a punk-rock Wordsworth, or a heavy-metal Milton, melding grandeur and the Grand Guignol, squalor and prophecy, in a kind of snarling sublime. In Caligulan, this voice fulfilled its potential: trash, noise, madness, death, and chaos create a kind of ambient howl, like a vortex within which characters flung hither and thither frantically try to make sense of their lives. The effect is at once uncanny and undeniably familiar. Reading Caligulan is something like walking the neighborhood while listening to the second movement of Shostakovich’s String Quartet No. 8 on repeat.

– The Hopkins Review

* * *

Bob Dylan, another poet who often takes the fugitive as a persona, put it this way: “To live outside the law you must be honest.” That begins to explain, for me, [Hilbert’s] identification with people on the fringe, gangsters, drunks and women who return to the men who batter them. He’s acknowledging that the poet in this place and age is a person on the fringe.

– Alfred Nicol, introduction at Newburyport Literary Festival, 2009

* * *

Foreword to the letterpress, signed/limited edition of Aim Your Arrows at the Sun:

To be haunted, for an American poet today, is a rare and enviable condition. Not by personal demons—everyone has those, and when poets write about them they are really haunting themselves. To be genuinely haunted, as Ernest Hilbert is in these outward- and backward-looking poems, one must be conscious of the past, and of the chastening contrast between the past and the present; in other words, one must have a sense of history. And history is the “bruising storm” that “matures” on the horizon of Hilbert’s poems, as he writes in “Selv’oscura,” while the poet remains “swaddled” in the untrustworthy comfort of the present.

When Hilbert is visited by the past it is by grand and violent phantoms: “I read on about the lives and deaths of kings,” he writes in a Lowellian phrase in “April Arsenal.” Like Robert Lowell, Hilbert is drawn to scenes of carnage, where the true face of humanity seems to reveal itself. A destroyed tank in the Sinai Desert has weathered into landscape, its “long-ago blow and loss” like an archeological reminder of the ways human beings, in the Middle East especially, keep returning to ancient patterns of violence: “proof that armies advanced this far / Before in the baffling waste,” as Hilbert puts it in “On Passing the Remains of a T-62 in the Sinai.” The scene rhymes with the “Normandy beachhead, beneath clouds of naval gunfire,” in “Surrender of Breda,” a poem titled after Velasquez’s masterpiece of a forgotten war.

But if the poet’s present seems much more peaceful than the poems’ past, Hilbert is not at all sure that is an advantage. The most savage poems in Aim Your Arrows at the Sun use the past’s grandeur to reproach the pettiness of our world. In the Juvenalian “Bread and Circuses,” Hilbert sees our TV shows and fast food as the equivalent of the largesse with which Rome’s rulers stupefied her people. “Gettysburg,” continuing the tradition of Civil War poems by Allen Tate and Lowell, contrasts the Union and Confederate dead with their parody reenactors: “The soldiers who fought that day / Weren’t plump. They didn’t wear wristwatches,” Hilbert observes.

After such humiliating contrasts, Hilbert and the reader can only take comfort in the truth stated in “Dining with Representatives of the Vatican Museum”—that it is art, including the art of poetry, that survives the past and incarnates it. Poems like the ones in Aim Your Arrows at the Sun are the “small remains of each man and each age” that remind us of what is past and passing, and that will represent us in times to come.

– Adam Kirsch, author of The Wounded Surgeon: Confession and Transformation in Six American Poets (Robert Lowell, Elizabeth Bishop, John Berryman, Randall Jarrell, Delmore Schwartz and Sylvia Plath)

* * *

Ernest Hilbert is so playful with his language, the profundity in his messages often sneaks up on you as you’re reading.

– Katie Darby Mullins, author of Neuro, Typical: Chemical Reactions and Trauma Bonds

* * *

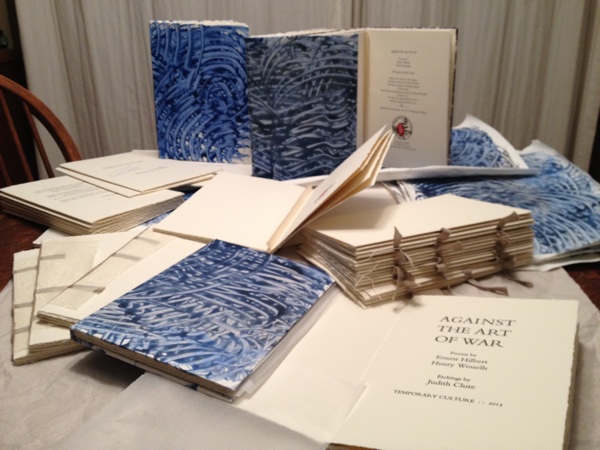

Opening a book by Ernest Hilbert is like walking into the home of a skilled carpenter. There is an immediate sense of craftsmanship, solidity. Things are not about to fall apart here. Yet Hilbert writes about the world we live in, where things often come undone in spectacular fashion. The tension between the well-made poem and the fractured world it evokes is only one of many tensions that charge his work with dramatic energy. Hilbert’s formal verses are like boxes of gunpowder fit to burst. “My heart is a meteorite,” he tells us. “I am its crater.” In his most recent book, Last One Out, even the poems of childhood offer imagery better suited to the battlefield than the playground. He writes of kids in “broken boots” whose dogs are leashed with frayed twine, in “scattered groups, like aimless parts / Of a convoy attacked from the air.” This is childhood as a war zone to be evacuated. At the center of the new collection is a poem titled “Against the Art of War,” in which Hilbert writes, “War begins and builds in all things,” and supports his claim with an extraordinary list poem. “It waits all summer in the young wasp’s tail, / On a tetanus-bristling nail,” he writes. He sees it in “The crouch and pounce of household cat, / The loser’s shoulders pinned to the mat, / The slippery floor of the slaughterhouse, / A trap pulled back for a mouse . . .” The poem goes on to say that it’s “as if we’re born for war and it for us.” Another poem, “Mars Ultor,” presents the vision of a world in which the god of war is the first to receive a sacrifice on imperial holidays. After all, “Law relies on guns / or must withdraw.” That is to say, where there is imperialism, war is inevitable. What other contemporary poet contemplates this kind of hard truth? I sometimes think of Ernest Hilbert as a poet of Empire. It’s not that he celebrates imperialism —who can read his poem, “On Passing the Remains of a T-62 in the Sinai,” without thinking of Shelley’s “Ozymandias”? Hilbert recognizes imperialism as an act of colossal hubris, but he chooses not to look past the evidence that ours is an imperialist nation. Here is another of his lists, this one of American battleships: “Maine rests at anchor in Yokohama, / Ohio in Suez, Kansas at Gibraltar.” The book’s title itself, Last One Out, makes one think of helicopters lifting people out of Vietnam. It is Hilbert’s unflinching gaze at realities not often considered in poetry that gives his work its heft and authority.

– Alfred Nicol, author of Winter Light

* * *

Hilbert’s unapologetically gorgeous fourth book shimmers with rich language, imagery, and insight . . . drawn to both beauty and dread, and always elemental. Last One Out speaks with a voice that is at once stately and humble, deeply connected and deeply solitary, unique.

– Asheville Poetry Review

* * *

From the outset these are poems of mood [Storm Swimmer], built on physical sensation. Nature, lovely or harsh, is set at times next to the violence of things commercial and pop-culture derived. Interestingly, in this book Hilbert doesn’t use the trademark “Hilbertian sonnet,” where rhymes come in tercets, cutting across the foursquare sonnet shape. Instead, he’s making new moves: many other invented stanza forms, in mix-and-match line lengths and rhyme schemes. He’s also still fond of mixing pop culture with high, heavy metal with Homer and Mozart, still the “hard drinker and high thinker” of Adam Kirsch’s phrase.

– The Hopkins Review

Hilbert’s debut, Sixty Sonnets made him something of a “bad boy” among the decorous New Formalists. The sonnets were saturated in alcohol, violence, literary allusion, and urban squalor; in them, muggers rub shoulders with fading academics. (Hilbert is neither, but perhaps on the outskirts of both highway robbery and scholarship: an antiquarian book dealer.) The 2013 All of You on the Good Earth sealed his promise as master of the modern American sonnet, but pushed his range of subject matter: all the brows—high, middle, and low—Science Fiction, pop-culture, academia, the TLS, Philadelphia neighborhoods, World War II, the Cold War. “Zeppelin” in a Hilbert poem could easily refer to either Count Ferdinand Von or Led.

– A. E. Stallings, author of Like: Poems

* * *

I first encountered Ernest Hilbert when I read Caligulan—a gorgeous work of precise image and meaning, exploring contemporary lives and ancient environs. Last One Out also examines powerful emotional circumstances of family love, then shoots distant arcs to relevant historical moments, as if distance is an essential way to contemplate one’s own burdens and riches. It’s a singular and satisfying read. Line by line, he seeks the extraordinary exchange, in simplicity and truth—human and moving.

– Ryan Blacketter, author of Horses All Over Hell: Stories

* * *

Engaging with Hilbert you quickly understand the wealth of knowledge he wields. Hilbert’s poetry matures with each new collection. His ear for music is unparalleled.

– Schuylkill Valley Journal

* * *

Hilbert’s book, Caligulan, came out a year before the last presidential election, but accurately predicts the anxiety of recent years, and provides language for us to talk about it. The title poem, in particular, embodies and enacts some of my own lifelong negative associations with the US: a sense of ubiquitous suffering, of being surveilled, of powerlessness and stress . . . . Anxiety transmits a sense of gruesome foreboding, of things that might happen. Hilbert’s poem admits, as Buddhism does, that suffering is omnipresent and death is inevitable, but then responds, “And so what?” After all, there will be a myriad of slight wounds every day of our lives. Perhaps it’s better just to face our Caligulan nightmares with a wry grin, and learn to befriend the dread.

– The Rumpus

* * *

In Caligulan one finds [Hilbert] exhibiting his expert rhyming skills, wide-ranging (and often darkly humorous) observations, and sharp-eyed, rhythmic lines. While the poems here are set in a general context of menace and disaster, one would be wrong to conclude that the book is in any way a “downer.” Hilbert knows how to poke fun and make jokes in the midst of the apocalypse.

– Daniel Klawitter

* * *

Who mixes transgression with formal constraints better than Ernest Hilbert? Answer: no one.

– Blake Wallin, author of No Sign on the Island

* * *

Ernest Hilbert, in two remarkable book-length sequences, Sixty Sonnets and All of You on the Good Earth, invents his own variation on the form, achieving a kind of early 21st-century upgrade.

– “Technology of the American Sonnet,” New Ohio Review

* * *

Hilbert’s work attains a high level of intensity through laser-sharp vision focused unsparingly on the detritus of post-modern life . . . . He has a pitch-perfect ear.

– Raintown Review

* * *

Ernest Hilbert is a Philadelphia poet who spent years writing free verse in the Allen Ginsberg vein, but his first book of poems, Sixty Sonnets (2009), is exactly what its title suggests. Earlier this year he published his second volume—also a set of 60 sonnets—called All Of You On The Good Earth. Hilbert experiments with how many ways he can prod, twist, and kick at the sonnet to pull the form into the 21st century.

– Peter Crimmins, “NewsWorks Tonight,” WHYY/NPR

* * *

Hilbert’s poems are good enough to choose virtues that run somewhat against the grain of present society. He portrays a remarkably witty and cool character on the downhill slide thrust upon our humanity by heartbreak and grief. At the same time, the presence of mind demonstrated by the composition of the poems and of Hilbert’s physical presence as a reader, affable and measured, reassure us of his survival, aplomb and fruition from that time of fire and rain.

– Boston Area Small Press and Poetry

* * *

Hilbert’s best work shows us the beauty in our failings.

– J.G. McClure

* * *

[Elegies & Laments is an] ingenious journey through sense and sound. One of the tracks records a particularly successful open mic where Hilbert reads, followed by stimulating contributions by Quincy R. Lehr, Paul Siegell, and Kristine Young. And introducing each track are tantalizing mashups of recordings, scratchy and haunting, of older poets, from Whitman to Ezra Pound to Sylvia Plath . . . The poems tend more toward the demotic and streetwise, but never lose Hilbert’s strong imagery, feel for cadence, and rhythmic firmness. A wonderful release.

– Synchronized Chaos

* * *

In Elegies & Laments, the music and poetry work together magically well, miraculously well. It’s a legitimate collaboration.

– Best American Poetry Blog

* * *

An album that defies genre . . . Elegies & Laments . . . is both in-your-face and ethereal. The crowning piece of the album is the last track, “Calavera for a Friend.” Backed by haunting strings, it captures the inevitability of death with heartbreaking candor. Elegies & Laments is an imaginative hybrid that anyone who appreciates poetry and/or music should put their ears to.

– PopMatters

* * *

There’s a cinematic depth to Elegies & Laments. Stand by your man, even when he throws your kitty-cat into a wood chipper, as happens in Hilbert’s sonnet “Domestic Situation.” An epic wah-wah guitar melts your god-damned face off and kills poetry dead. There’s too much seething dread, and I’m developing an uncomfortable hotness-under-the-collar from the nagging suspicion that I’m being called out for being under-prepared for life, in a way I’m not educated enough to fully understand. Hilbert’s cleverly induced a low-level PTSD with his insidious record.

– Raintown Review

* * *

Hilbert’s sonnets recall a range of work from Baudelaire and Robert Lowell to Henri Cole. Baudelaire counterpoints the formal perfection of the traditional French sonnet against nightmare-scapes of 1850s Paris to embody that tension within himself which lends the title to the longest section of Les Fleurs du Mal : i.e., Spleen et Idéal. Lowell’s blank verse sonnets generally maintain the English-language sonnet’s traditional iambic pentameter, though often roughing the meter up and abandoning rhyme in order to express a similar tension between the extra-temporal ideal and history’s broken reality. Henri Cole, especially in the breakthrough books The Visible Man and Middle Earth, uses an un-metered and unrhymed 14-line “sonnet” to enact similar tensions between abstract perfection and material imperfection, the life of the mind and the life of the body.

– The Hopkins Review

* * *

I loved Caligulan. There is something so satisfying about the rhythm and form of these poems, like they’re cut in stone. The book reminds me of what I love about Don Paterson, Heaney, and Larkin (and Bishop!).

– John Wall Barger, author of The Book of Festus

* * *

Persevering with the sonnet, while evoking the hero-wanderer of epic, Hilbert reserves his promise to sing the songs of, as Seamus Heaney phrased it, “single things,” of the poet’s dilemma as it is, without agonizing much in the modal auxiliaries of “may,” “might,” or “should” . . . Hilbert’s poems are good enough to choose virtues that run somewhat against the grain of present society. He portrays a remarkably witty and cool character on the downhill slide thrust upon our humanity by heartbreak and grief.

– Boston Area Small Press and Poetry Scene

* * *

Amazing and innovative . . . The music is variegated and fascinating, by turns vicious and lovely . . . [it does] what art should do: change things. Elegies & Laments will change you, too.

– Literary Magnet

* * *

“Notes of an Associative Reader” Contributor’s Marginalia: Peter Vertacnik responding to Ernest Hilbert’s “Vertebrate”

Sound comes first. I’ve read this poem out loud over a dozen times. Like the pilot whale of its extended simile, it communicates through a kind of echolocation. Even mute skimming allows its speech to seep in, as through a water-logged ear. Line after line, words call to each other in their muffled way: “fossil” to “invisible,” “gulls” to “bulbs,” “vaults” to “caught,” “hibiscus” to “lettuce” to “hiss,” “purslane” to “spine.”

***

Slant melody, but melody still. Reading “Vertebrate” I am reminded, perhaps oddly, of Camille Saint-Saëns’ final works, sonatas for oboe, clarinet, and bassoon: light melodies when compared to what was rampant then—Stravinsky’s dissonance, Ravel’s amputated concerto—but not slight, composed for the hollow, reeded bones of woodwinds. “At the moment,” Saint-Saëns wrote to his friend, Chantavoine, in April, 1921, “I am concentrating my last reserves on giving rarely considered instruments the chance to be heard.” And so may this poem for its lounging man, for its stranded, stripped skeleton.

***

“Smothered now by common purslane, sinking / Hiss of sand that slowly swallows the great spine.”

Stop thinking about “Ozymandias!”

***

But it does send me back to other poems. It scuffs the set surface of my mind with its associations.

Pilot whales are more dolphins than whales, I tell myself. And yet two (very different) whale poems occur to me almost immediately: A.D. Hope’s “The Cetaceans” and W.S. Merwin’s “For a Coming Extinction.” And when I read, in the latter poem, “When you have left the seas nodding on their stalks,” I am sent back to “Bumped by newborn bulbs of sea hibiscus.” More muffled connections.

I think, too, of Milton’s epic simile from Book 1 of Paradise Lost, that of Satan lying chained on Hell’s burning lake—but also of “The Pilot of some small night-founder’d Skiff” so close to a danger he doesn’t recognize. That’s a bit of a stretch, another part of my brain complains, though I continue reading.

“And longing, and an essential flicker / of life’s movement and radiance ran through—” reminds me of E.A. Robinson’s sonnet of fragile consecration, which in turn recalls George Crabbe’s heroic couplets. Tall stacks of books extend their varied spines (spines made of spines!) precariously higher beside me.

***

Couplets like vertebrae!

Couplets like vertebrae!

***

Some poems I covet for a line or a rhyme-pair, for a sly turn of phrase or metaphor. But my envy for “Vertebrate” feels encompassing; the temptation to scavenge is keen.

***

A Sunday evening decades ago. Late fall or early winter. My father dozes on his side in front of our fireplace. The carpet on the living room floor is deeply worn, even singed in places near the hearth by the escape of errant sparks. Light vaults from the flames’ essential flicker behind a mesh-iron screen. Even lying down he seems giant, his vast flannelled belly sloping out from his spine, both mountain and shadow. But as the burning logs crackle at random so too will his hip when he rises soon to finish his nap on the recliner. He’s much older than my friends’ fathers, mid-fifties and graying towards the sparseness of age, work and time curving his vertebrae. When he sits at the dinner table or in backyard shade, his stories still swarm, but his breathing now is filled with the hiss of embers-to-ashes.

* * *

FULL CAREER BIOGRAPHY

2012-2015

Ernest Hilbert’s third full-length poetry collection, Caligulan, was published in hardcover by Measure Press in September 2015. Poems from the collection appeared in American Arts Quarterly, American Poetry Review, Asheville Poetry Review, At Length, Battersea Review, Birmingham Poetry Review, Boston Review, Clarion, Cleaver, Dark Horse, Edinburgh Review, Hopkins Review, Hudson Review, Measure, Parnassus, Philadelphia Inquirer, Listen: Life with Classical Music, New Criterion, Smartish Pace, and Yale Review.

In May 2015, Hilbert’s second opera with Stella Sung, The Book Collector, received ten days of workshops at the Dayton Performing Arts Alliance (Ballet, Opera, Philharmonic), which commissioned the work with help from the League of American Orchestras, New Music USA, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Francis Goelet Charitable Lead Trusts, the Aaron Copland Fund for Music, and the ASCAP Foundation. The opera, which incorporates 3-D digital technology and a ballet, is a historical tragedy intended as companion piece to Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana. It will premiere in May, 2016.

In 2013, The Red Silk Thread, the first opera by composer Stella Sung with a libretto by Hilbert received two public workshop productions at the Michigan Opera Studio at Ann Arbor. A fully-staged production took place in April 2014 at the Curtis M. Phillips Center for Performing Arts in Gainesville, Florida, with 70-piece orchestra, 60-voice offstage choir, and a cast of professional singers. Hilbert delivered a pre-concert lecture on the role of the librettist and also gave a talk one morning on the making of a modern opera for 1,000 local school children.

Ernest Hilbert’s second full-length poetry collection, All of You on the Good Earth, appeared in April 2013 from Red Hen Press. Poems from the collection appeared in 32 Poems, 66: The Journal of the Sonnet, American Poetry Review, Asheville Poetry Review, Battersea Review, Cimarron Review, Georgetown Review, Harvard Review, Horizon Review (London), Jewish Quarterly (London), Linebreak, Measure, New Ohio Review, Parnassus, Poetry East, RATTLE, The Dark Horse, The London Magazine, The New Criterion, The Oxonian Review, and The Yale Review.

Hilbert also released a spoken word album in 2013 with Philadelphia record label Pub Can. Elegies & Laments features performances of Hilbert’s poems by the author as well as several guest readers with a variety of musical accompaniment, including jazz, indie rock, and classical music by two songwriters and a classical composer. The album is available on vinyl, compact disc, digital download, and through streaming services.